I am a neurodivergent engineering manager who loves to innovate and solve problems. But, I am also a neurodivergent person who navigates daily hurdles that stem from processing social cues differently, managing sensory sensitivities, and requiring support for information processing and executive functioning. I live in both these realities, at once.

My productivity and creativity flourish when I have access to the right tools and environments. Adjustable screen brightness, customizable fonts, noise-canceling features, and variable playback speeds aren’t mere conveniences—they’re essential bridges to effective work. Text-to-speech and speech-to-text technologies don’t just ease my anxiety about note-taking or auditory processing; they free my mind to focus on what truly matters: innovation and problem-solving.

I am truly grateful for the presence and continuous growth of technology that makes my work easier on different fronts. Without these accessibility features, simple tasks become arduous journeys. I find myself watching videos repeatedly to create my own closed captions, frequently interrupting conversations to clarify words I couldn’t process, or spending hours crafting alternative formats of content. What might take others an hour can consume five of mine, not just draining time and energy, but also taking an emotional toll. Each of these moments reinforces a sense of being out of step with a world not designed for minds like mine.

Beyond Features: Accessibility as Foundation of Design and its relationship with Psychological Safety

Accessibility isn’t an extra—it’s an essential. By “extra”, I mean that it isn’t a special accommodation for a minority, it’s simply good design that benefits all. The Center of Excellence for Universal Design emphasizes exactly that:

“Universal Design (UD) is the design and composition of an environment so that it can be accessed, understood and used to the greatest extent possible by all people regardless of their age, size, ability or disability. … This is not a special requirement, for the benefit of only a minority of the population. It is a fundamental condition of good design.”

The Relationship Between Accessibility and Psychological Safety

While the connection between accessibility and inclusion might seem obvious, the relationship between accessibility and psychological safety is nuanced, and powerful – and it goes both ways.

This relationship manifests in several key ways:

Basic accessibility creates a foundation for psychological safety. When people can perform essential tasks independently, they develop the confidence and security needed to fully participate in their environment.

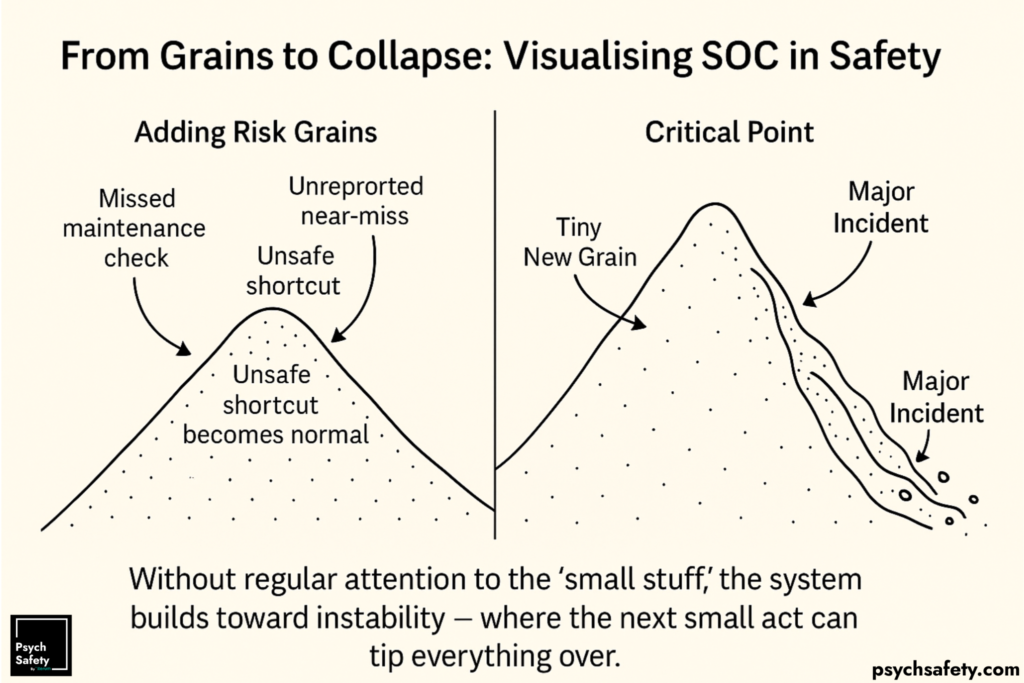

This isn’t a linear progression, but a complex, interconnected system.

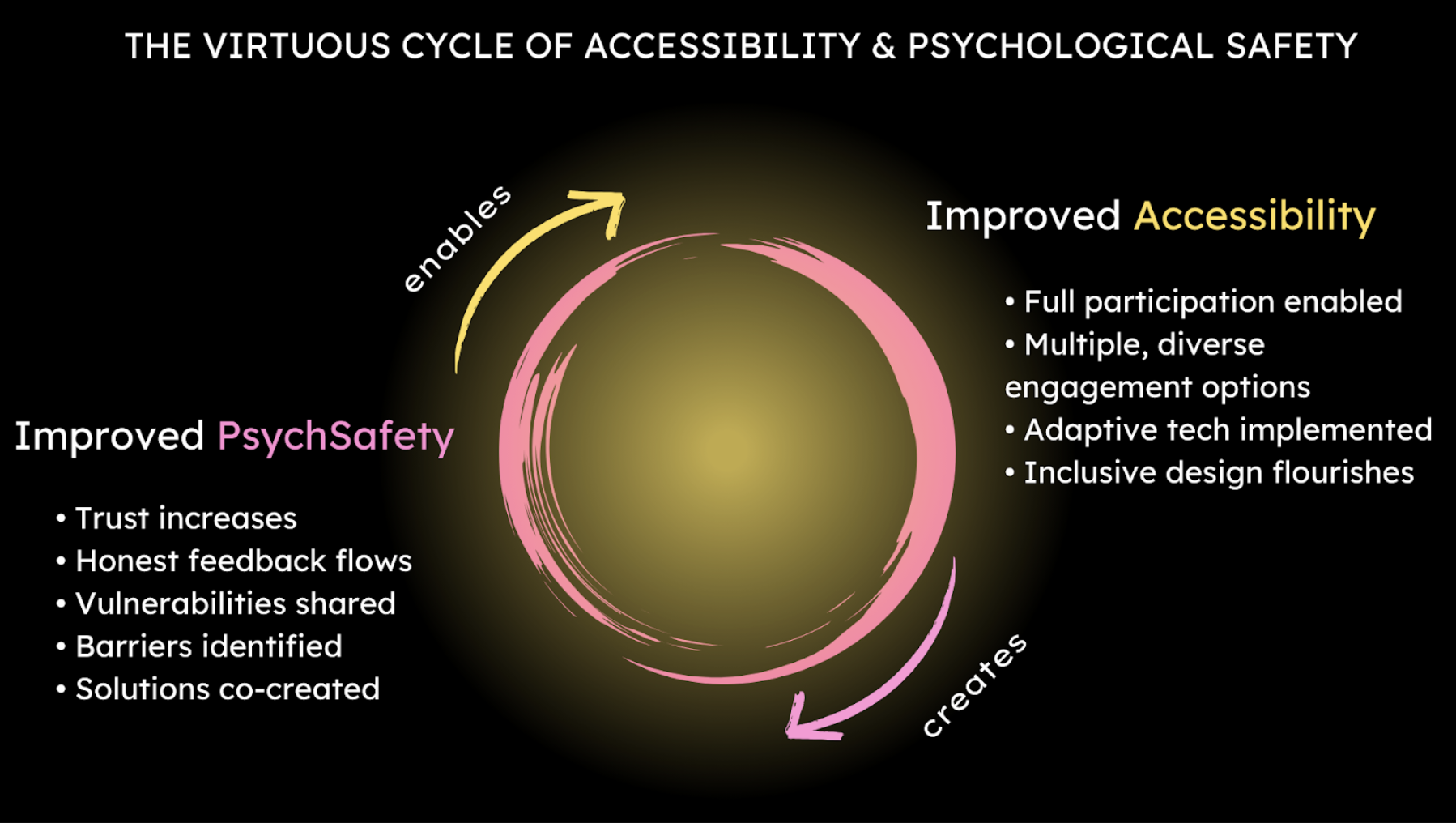

The relationship between accessibility and psychological safety is profoundly symbiotic. Each improvement in accessibility creates more psychological safety, which in turn generates more sophisticated accessibility mechanisms. For example:

- Meeting Support Systems: When a team normalizes using meeting captions, team members with auditory processing difficulties feel confident participating fully. This psychological safety encourages them to suggest additional improvements, like having key points shared in writing beforehand, leading to more inclusive meeting practices that benefit everyone.

- Flexible Work Arrangements: When flexible work hours become standard practice, employees managing chronic conditions can confidently arrange their schedules to match their energy levels without feeling judged. This openness often leads to conversations about other workplace adaptations, like creating quiet rest spaces or offering remote work options.

- Communication Preferences: As teams establish clear communication guidelines, people naturally begin sharing their needs as part of the workplace culture. Someone might explain that while instant messages work well for quick questions, they prefer scheduled video calls for complex discussions, helping the team develop more effective communication patterns. This opens the doors to reimagining an inclusive team culture.

- Physical Workspace Design: When teams create adaptable workspaces, people feel safe expressing their environmental needs. For instance, someone might share that while standing desks help, better lighting would make an even bigger difference – leading to workplace improvements that might have gone unnoticed in a less supportive environment.

- Technology Adaptations: As organizations normalize discussions about digital accessibility, team members feel comfortable explaining their challenges with certain tools. This psychological safety leads to collaborative problem-solving, where someone might suggest that while screen readers are helpful, customizable interfaces would provide even better support for different needs.

These examples call for a necessary distinction between how we define accessibility measures and inclusive practices. So, I’d like to clarify: Taking accessibility measures is just ticking a box. But, when done with intention, they create psychological safety. Consequently, inclusion happens naturally. I find it hard to draw lines accessibility, psychological safety, and inclusion (except when I look at the psychological safety pyramid). But what I can distinguish is intent and the absence of it.

It’s a virtuous cycle of continuous adaptation and understanding – where removing barriers invites people to bring their authentic selves into work, in addition to creating physical access. In accessible spaces, I can arrive and be as myself, because I have all the support I need.

An important note:

- A technically accessible space might still lack psychological safety

For example, a company might have all the right physical accommodations – ramps, adjustable desks, screen readers – but if a manager publicly questions why someone needs to use text-to-speech software or makes comments about how accommodations slow down the team, people won’t feel safe using these tools even though they’re available.

- A psychologically safe environment might remain inaccessible to some

Picture a friendly, supportive startup where everyone feels comfortable sharing ideas and making mistakes. However, they only hold in-person meetings in a second-floor office with no elevator, effectively excluding team members who use wheelchairs. Or imagine a team that prides itself on open communication but only shares important updates through quick hallway conversations, making it difficult for remote workers or people with hearing impairments to stay informed.

- True accessibility often nurtures psychological safety by demonstrating respect and consideration for diverse needs

Consider a company that proactively asks all employees about their communication preferences during onboarding. They create standard practices like providing meeting agendas in advance, offering both written and verbal instructions for projects, and making it normal to state access needs (“I need captions for this call” or “Could you send that in writing?”). When these practices become routine, people naturally feel respected and safe asking for what they need to work effectively.

Remember: the goal isn’t just to tick boxes for accessibility compliance, but to create an environment where everyone feels secure enough to speak up about what they need to do their best work. This opens the door to true inclusion and superior performance.

Throughout my journey, what I’ve learned is that accessibility and psychological safety aren’t separate concepts. They’re more like a living, breathing ecosystem that continuously transforms itself—a dynamic interplay where each improvement creates space for more authentic engagement, more profound understanding, and more innovative solutions.

The post Accessibility: A Road to Psychological Safety appeared first on Psych Safety.