All Models Are Wrong, and Some Are Useful

By Tom Geraghty

This is one of my favourite, and most often used, aphorisms. It’s attributed to George Box, a British statistician, from a 1976 paper on Science and Statistics, though the idea predates Box considerably. Alfred Korzybski famously stated in 1933:

“A map is not the territory it represents, but, if correct, it has a similar structure to the territory, which accounts for its usefulness.”

And Walter Shewhart, Deming’s mentor and the creator of the PDSA cycle, stated in a 1939 paper,

“any such model is always an incomplete though useful picture of the conceived physical thing.”

However what Box wrote about models in 1976 captures the idea brilliantly:

“Since all models are wrong the scientist must be alert to what is importantly wrong. It is inappropriate to be concerned about mice when there are tigers abroad.”

I love this. What he is saying is that models always fall short of the complexities of reality, but may be useful nonetheless.

What is a model?

A model is a simplification, a representation, of reality, intended to foster greater understanding and/or decision making. It may be mathematical (see Anscombe’s quartet for a great example of when a single statistic belies very different underlying data), graphical, or even literary or metaphorical. Every model should offer some utility: for example, an aid to understanding or decision making, making predictions, or informing actions. And although all models are wrong, a model’s degree of wrongness may not necessarily be relative to its utility. There are cases where a very wrong model may be useful (even the wrong map, in rare cases), but others where we might have a very “right”, highly precise model that’s not actually much use at all.

“Ce qui est simple est toujours faux. Ce qui ne l’est pas est inutilisable”

Paul Valéry (1871–1945)

We should not prioritise precision over utility, and we tend to intuitively understand that. If we didn’t, we would have no maps, for one thing. The most accurate map would be a direct, one-to-one copy of the real world, and would not be particularly useful (unless maybe you’re attempting to work out the Ultimate Question of Life, the Universe, and Everything.) It is in fact the reduction of nuance and detail which makes the map useful and usable in practice.

“As a model of a complex system becomes more complete, it becomes less understandable. Alternatively, as a model grows more realistic, it also becomes just as difficult to understand as the real-world processes it represents.”

Bonini’s paradox, named after Stanford business professor Charles Bonini

It’s probably also wise to differentiate between models and frameworks. Models primarily explain some real-world phenomena – why things work in a certain way – and have some utility in practice, whilst frameworks are primarily practice tools: structured approaches and guidelines. Frameworks inform and shape how we work with a certain phenomenon, but they don’t necessarily provide insight into why. In practice, there’s often an overlap between the two.

The usefulness (or not) of models

This is not to say that every model is useful, and it’s important to recognise that not all models are equal. We can, to a degree, evaluate the usefulness of a model by considering a few questions:

- How long has the model existed? Generally, the longer a model exists for, the greater it’s been evaluated and tested, and thus is more likely to be robust and/or have greater utility.

- How easy is it for practitioners to understand and use? Theoretical models are great, but practice makes the world go round. If a model is too complicated for people to use in practice, it’s probably not that useful. There is a trade-off between a model’s precision and its ease of use; to adapt Occam’s Razor: the simplest model is often the best.

- Where did it come from? Many good models are based on scientific enquiry and/or deep practitioner expertise and insight. Both are good. However models that are commercialised or trademarked should be treated with caution, especially if the use or adaptation of them comes with a fee.

Thus, we can elaborate on Box’s all models are wrong and some are useful, and additionally state:

Some models are more wrong than others.

And because it is not always easy to be aware of which aspect of a model is “importantly wrong,” we should be very careful about how we apply models in practice. Many models are excellent thinking tools, and provide a scaffold for us to think more deeply and critically about complex dynamics: we are simple beings and none of us can fully comprehend complex sociotechnical dynamics, so models help us to turn understanding into practice.

Using models

General relativity provides us with an incredibly useful, successful and (somewhat) simple model of gravitation and cosmology, but it is incomplete and breaks down in certain circumstances, such as inside black holes..

In group psychology, Tuckman’s model is a great example of the utility of a model of interpersonal dynamics. It’s clearly ‘wrong.’ It’s a dramatic oversimplification of complex real-world team relationships and interactions, and doesn’t apply equally across different contexts. But Tuckman’s model helps us understand that groups of people need time, practice, and the establishment of shared norms and language in order to become high performing teams, and that changes to the team’s context or environment can push the team “back” into previous stages. Sometimes, the most useful thing about Tuckman’s model is seeing it and being able to relate it to your own experiences and situations with teams – it can help you reflect on which “stage” you’re at and therefore consider the path forwards.

What that looks like in practice will be very different, depending on context. But by using Tuckman’s as a scaffold, we can experiment with ways to flow better or faster through the forming-storming-norming stages to get to ‘performing’, even if they’re not “real” stages. This (analogous to Amy Edmondson’s concept of Teaming) is applied in practice in many domains including surgery and aviation, where teams often come together rapidly with little prior acquaintance of each other, and need to perform well, in a short period of time. There are lots of practices that contribute to this, from simple icebreakers to personal user manuals, team charters, and more.

When models create problems

Using a knowingly wrong model well can be powerful, but what if the model is very wrong, and we are not alert to it? By extension to All models are wrong, some are useful, and some are more wrong than others:

Some models may be harmful.

When we apply models as practical interventions rather than thinking tools, we should be confident that the model is as right as necessary. And we also need to adopt a humble and experimental mindset, acknowledging that the model we adopted may not prove helpful, and indeed may even be harmful.

For example, we know many people come across the concept of psychological safety through the “Four Stages” model. This model is useful in two significant ways:

- It begins to build a language around psychological safety, which some find helpful for starting conversations about it.

- It includes the idea that psychological safety is not a simple binary of feeling safe or not safe: it exists in different degrees and dimensions in groups of people, and varies over time.

However, the model has its limitations and in some cases can do more harm than good. We have had a number of clients come to us after struggling to work through the four stages model of “inclusion – learner – contributor – challenger” and finding that it hasn’t worked for them. For many, the linear journey model of psychological safety which implies that teams progress through the “stages” doesn’t match their experience of trying to foster psychological safety in real-world contexts. Some teams might find it relatively easy to challenge each other, for example, but far more intimidating to speak up to contribute ideas, or admit they don’t know something. Trying to impose a model which doesn’t fit can lead to frustration, wasted effort and potentially disillusionment with the idea of psychological safety.

What use are wrong models?

We can still use models that are wrong, as long as we do it knowingly, and they can even help us develop more discernment and criticality, deepening our overall understanding of a concept and our lived experience of it. An analogy would be asking people to examine the flat earth model – why humanity might once have accepted it, and where it breaks down in reality; in examining why a model doesn’t reflect the real world, we build a greater understanding of what the world is really like.

We find Tuckman’s Model generally more useful and more widely applicable in practice than the Four Stages model of psychological safety, so we tend to use it more. However, if the Four Stages model comes up in workshops, we discuss it alongside Box’s aphorism of “All models are wrong and some are useful”. This lets us ask how the Four Stages model both works and doesn’t work in practice. This allows for a very safe and interesting exploration of the psychological safety concept, where participants get to draw on their own insights, perspectives and experiences.

All models are wrong, but some are useful.

Ultimately, we should probably focus more on intelligently applying and improving imperfect models to everyday life, rather than worrying whether a model is perfectly correct in all cases. The latter results only in endless debate, whilst the former allows us to continuously learn and improve.

Related Reading:

Sociotechnical Theory

Deming’s 14 Points of Management

Tuckman’s Model

Icebreakers

Psychological Safety in Aviation

Personal User Manuals

Psychological Safety: Team Charters

The Four Stages of Psychological Safety

It’s only a model

Open Enrolment Online Workshops

Booking now for 10th – 27th March 2025

Looking to deepen your expertise in psychological safety—whether for your team, your organisation, or your own practice? Our flagship Complete Psychological Safety Course: Train the Trainer is designed for leaders, trainers, and consultants who want to create safer, more effective workplaces.

This flexible programme consists of six interactive 2.5-hour online workshops, each offering a different lens on how to understand, foster, build, maintain, and measure psychological safety—as well as how to inspire others to do the same. You can join individual sessions relevant to your role or take the full programme to gain a comprehensive Train the Trainer package.

Whether you’re:

- A leader or manager looking to foster a high-performing, open culture in your organisation,

- A team member wanting to integrate psychological safety into all aspects of your work

- An internal trainer or facilitator developing teams and embedding psychological safety across your workplace, or

- An independent coach or consultant wanting to deliver psychological safety training for your own clients,

… this programme gives you the practical tools, expert guidance, and real-world applications to make an impact.

Secure your spot today and start building psychologically safer, more inclusive spaces for meaningful work.

All our workshops provide certificated CPD hours and Credly badges to evidence your professional development.

Psychological Safety in Practice

Aviation: Does complacency really cause errors?

This fantastic piece by Alex Pollitt argues that “complacency” in aviation is often blamed for errors or accidents but rarely defined or understood in any meaningful way. It suggests complacency is not a root cause but rather a symptom. Despite frequent references to complacency in accident reports and safety training, no one has actually systematically broken down how it arises, how it causes lapses in attention, or why it fosters overconfidence.

Telling pilots simply to “be less complacent” or “be more vigilant” is unhelpfully simplistic; meaningful progress would require examining the deeper conditions (equipment, goals, pressures, resources, and culture) that give rise to “complacency” in the first place.

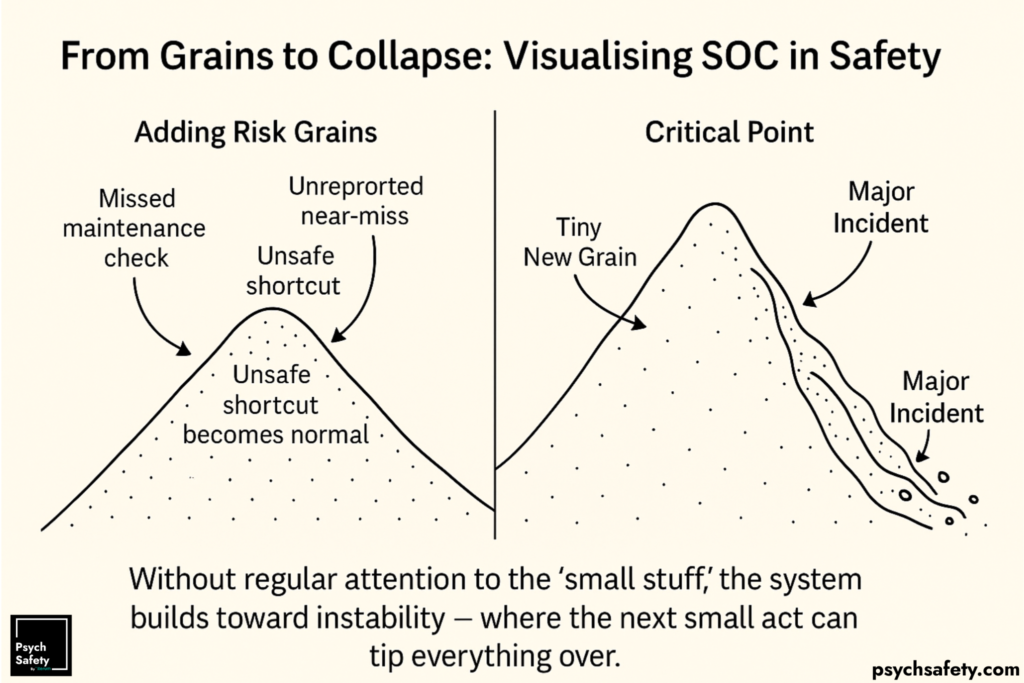

Preempting Problems in a Sociotechnical System

I love this case study of an incident by Nick Travaglini at Honeycomb.io because it really gets into the idea of sociotechnicality, production pressure, adaptive capacity, and even how to actually decide if something is an incident at all.

Accessibility and Psychological Safety

Thanks so much to our own Navya Adhikarla for this great piece examining her own relationship with work, psychological safety and accessibility. Basic accessibility creates a foundation for psychological safety. When people can perform essential tasks independently, they develop the confidence and security needed to fully participate in their environment.

This week’s poem:

Hard Day On The Planet lyrics, by Loudon Wainwright III, 1986

The dollar went down and the President said

“Who’s in charge, now?” I don’t know, take your pick

A new disease every day and the old ones are coming back

Things are looking kind of gray, like they’re going to black

Don’t turn on the TV, don’t show me the paper

(I) Don’t want to know he got kidnapped or why they all raped her

I want to go on vacation till the pressure lets up

But they keep hijacking airplanes and blowing them up

It’s been a hard day on the planet

How much is it all worth?

It’s getting harder to understand it

Things are tough all over on earth

It’s hot in December and cold in July

When it rains it pours out of a poisonous sky

In California the body counts keep getting higher

It’s evil out there, man that state is always on fire

Everyone has a system, but they can’t seem to win

Even Bob Geldof looks alarmingly thin

I got to get on that shuttle get me out of this place

But there’s gonna be warfare up there in outer space

It’s been a hard day on the planet

How much is it all worth?

It’s getting harder to understand it

Things are tough all over on earth

I’ve got clothes on my back and shoes on my feet

A roof over my head and something to eat

My kids are all healthy and my folks are alive

You know, it’s amazing but sometimes I think I’ll survive

I’ve got all of my fingers and all of my toes

I’m pretty well off I guess, I suppose

So how come I feel bad so much of the time?

A man ain’t an island John Dunn wasn’t lying

It’s been a hard day on the planet

How much is it all worth?

It’s getting harder to understand it

Things are tough all over on earth

It’s business as usual; some things never change

It’s unfair, it’s tough, unkind and it’s strange

We don’t seem to learn; we can’t seem to stop

Maybe some explosions would close up the shop

You know, maybe that would be fine: we would be off the hook

We resolved all our problems, never mind what it took

And it all would be over, finito, the end

Until the survivors started up all over again

It’s been a hard day on the planet

How much is it all worth?

It’s getting harder to understand it

Things are tough all over on earth.

Listen to Hard Day On The Planet on Youtube.

The post All Models Are Wrong, and Some Are Harmful appeared first on Psych Safety.