Blametropism

By Tom Geraghty, edited by Jade Garratt

It’s a common fallacy that psychological safety means having a “blameless” culture.

Just like so many misconceptions around psychological safety, that’s not actually the case. Sometimes we can’t avoid blame and, on some occasions, it might even be appropriate and/or useful. For example, if an employee deliberately steals cash from the register, we can, and should, “blame” them for doing so and impose appropriate consequences. This doesn’t negate psychological safety – it actually helps foster it by reinforcing robust guardrails of behaviour. There might also be occasions where people in organisations hurt, harm, or cheat others, with the intent to do so. Blame may be appropriate when they cause or risk harm, and, to use the legal terms, possess the mens rea (the intention) and the actus reus (the action) in doing so. In these cases, setting and upholding high standards of behaviour not only improves outcomes and safety, but also improves psychological safety by making it explicitly clear what types of behaviour are acceptable and unacceptable in the organisation.

We define blame as “accountability without context“

We humans also possess a deep-seated instinct to apportion blame, even when it isn’t necessarily useful or appropriate. This phenomenon we call blametropism, from the Latin word tropus and the English -ism. Tropism relates to turning, or having an affinity or propensity for something (as in “heliotropic” for plants turning toward the sun, or “neurotropic” for viruses that affect nerve tissue).

We are all blametropic. Blametropism is a very common, possibly ubiquitous human instinct. Particularly in Western cultures, there is often a strong temptation to attribute the cause of an adverse event to someone’s individual actions. Tendencies towards both individualism and a propensity for litigation, such as we see in the USA, exacerbate this. It’s also more common in some industries than others: blametropism is especially prevalent in healthcare for example, but arguably less so broadly in technology (though certainly still very common!).

Blametropism means that if someone deviates from the “right” way of doing things, either by deviating from the official protocol or simply away from the accepted “way we do things”, our instinct is to feel that they were wrong, and blame them. We see their violation of “the rules” as evidence that they are a bad person with malintent.

We see blametropism in formal incident investigations too. When an incident occurs in a sociotechnical system – an organisation, a production line, or a passenger aircraft – it’s almost always a complex result of a compounding of multiple causal and dependent factors. This includes technical, environmental and human factors, alongside others. All too frequently however, investigations into incidents simply find that “the human did it.”

“Since no system has ever built itself, since few systems operate by themselves, and since no systems maintain themselves, the search for a human in the path of failure is bound to succeed.”

Hollnagel & Woods, 2005

Why is blametropism a problem?

The main questions we want to ask ourselves here are is the blame fair, and is it useful?

In Bernard Williams essay “Moral Luck”, he notes that we often blame others for outcomes which are in fact heavily influenced by factors beyond their control.

“Social psychological studies have consistently found that people have a strong tendency to overestimate internal factors, such as one’s disposition, and underestimate the external factors driving people’s behavior”

In other words, if someone does something that appears wrong to us, we attribute to their character what can be better explained by the context in which they were acting. This is essentially the fundamental attribution error, which we’ve covered previously, and means that our blame may well be an unfair judgement.

This effect is amplified when we encounter people who don’t behave like us. We make generalised and rapid inferences about other people’s states of mind when assigning blame, and because we explain our own actions more through context than character, people who don’t behave like us may appear to be less influenced by context. This connects also to the “Ultimate Attribution Error”: if someone belongs to a conspicuous (e.g., minority) social group (an “marked identity”, to use Deborah Cameron’s terms), the cause of failure may be attributed to the traits of that group. We are therefore more likely to assign their mistakes to their character or the perceived traits of their group, rather than giving the attention we should to the context of the work and the systems they were operating within. We may even believe that when they didn’t behave as we would, and the outcome was negative, it’s their fault, but if the outcome was positive, they simply got lucky.

Blame and Intention

Blame is inextricably linked to intent. As Aristotle describes in Nicomachean Ethics – blame presupposes that someone had control over, and knowledge of, their actions. We seek to blame those who intentionally do “wrong”, and thus when we blame, we imply or assume that the person had bad intent. This is intrinsically linked to our notions of justice. As in the mens rea concept mentioned above, most serious offences, with some exceptions, require someone to intend to commit the crime as well as actually commit it. Intent may also be a recklessness or indifference as to the harm that their actions could cause. There is a difference between the acts of someone who intended to cause harm, and healthcare workers who recklessly cause harm or death, but it doesn’t make a lot of difference to the first and second victims – the families, friends, and other workers.

However, more often than not, in the case of incidents and things going wrong in complex systems, the person found to be “at fault” had no intention to cause harm or failure. Maybe they slipped or lapsed (none of us are perfect, and we never will be), and even if they knowingly violated a process or protocol, the likelihood is their intention was “good” (in their own context) – perhaps they were under pressure to achieve multiple competing goals (e.g. speed and safety), or perhaps part of the system failed and they were forced to find a workaround in the moment.

This brings us on to the question of the usefulness of blame. If we jump to blame, we can easily miss all this nuance and any opportunities to better understand and learn from the multitude of compounding factors. Not only is blame often unfairly attributed, but when blame is our conclusion, and we stop at “blame the human” we crucially forget to explore why the human in the system did what they did. In failing to do that, we miss the opportunity to prevent similar mistakes happening again.

Is blame ever useful?

Some argue that punitive consequences assist in improving safety and preventing adverse outcomes. There might be some truth in this, but not a lot. And it’s worth acknowledging that there might be rare situations where blame can assist learning. The shame that we feel when we have done wrong, harmed or hurt someone or risked doing so, is a powerful force. An appropriate level of blame, either imposed by others or upon ourselves, may sometimes be a powerful way to embed behaviour change and remind ourselves to do it differently next time.

But there are some real dangers with this approach. One is that as we’ve already found, it’s very easy to overdo blame. Instead of fostering learning, this may instead foster resentment and damage confidence in someone’s capability or self-worth. Ultimately, this can lead to poorer performance, damage the team culture and affect mental health and wellbeing. What’s more, publicly-imposed blame is likely to teach others to hide their mistakes, suppress their concerns, and “keep their head down” lest they suffer the same public humiliation.

It partly comes down to whether we want to learn just from this single event, or all future events. Usually, we want to create the conditions where we can keep learning and keep improving. And in order to do that, we need to create conditions where people feel safe enough to own their mistakes, share them and help others learn from them. Given this, it’s clear to see why we say that inappropriate and excessive blame is one of the seven deadly sins of psychological safety.

“Being blamed in the context of a safety investigation is contrary to the purpose of a safety investigation, partly because it is deathly for an occurrence reporting system, and for any subsequent investigations and learning.”

Dr Steven Shorrock, Just Culture: Who are we really afraid of? 2016

Overcoming blametropism

This tendency towards blame mirrors our desire to identify a single core root cause of an incident or outcome. We have a desire to make sense of the world and believe that everything has a just cause: we tend to dislike ambiguity and complexity, in particular because it makes it difficult to assign causality.

Nietzsche considered blame, along with guilt and resentment, as part of a human morality born out of weakness – he believed that our human inclination to blame arises from ingrained social conditioning as well as power dynamics, not from some absolute moral truth. For him, our disposition to blame is tied to cultural and social forces, and we can strive to “overcome this primitive instinct” for blametropism.

Beyond blametropism

When blame takes priority, any attempts to improve learning or future outcomes become secondary to our need to impose some kind of natural justice. So what’s the alternative?

A far more constructive and utilitarian approach is to treat errors, mistakes and violations as sources of valuable information about the system. They may well be an indicator that we need to better design the systems so they make it easier to do the right thing and don’t necessitate violations, or, since no system is ever perfect, build in functions that support workers when they are forced to work around flawed systems.

In most cases, from the perspective of what is actually most useful – i.e. what approach engenders the best learning from a failure or incident, blame is very rarely required, however it is often imposed due to a deep-seated instinctive and sometimes ideological belief that it’s necessary. This blame is often unfair and unjust, and can distract us from identifying and addressing broader systemic issues. Even if blame is “justified”, psychological safety as a concept, and Just Culture, HOP Learning Teams and similar approaches are primarily concerned with learning and improving. Justice is a not insignificant, but secondary, concern after learning and improving.

We might never completely transcend our tendency to want to blame, but we can acknowledge it, and intentionally work on more useful, learning-focused alternatives. This is why in practice, we prefer to promote “blame-aware” practices and approaches. By trusting in the other human that they could but will not judge, we’re creating the space for collective learning.

Context and Local Rationality

Blame can be considered “accountability without context“, so a powerful way to address blame is to actively and explicitly consider context. Keeping the Local Rationality Principle at the forefront of our minds while investigating incidents helps us maintain a curious and open approach to failure and adverse events. We assume positive intent where possible, but also recognise that it’s possible for people to not share the same positive goals as us, on occasion. Sometimes (thankfully rarely however) people do actually intend to cause harm, and we can deal with that appropriately.

By recognising our own inherent blametropism – our innate instinct to apportion blame – and becoming blame-aware instead of (maybe naively) attempting to be entirely blameless or blame-free, we can check in with ourselves and others to help determine whether we’re blaming because it’ll make us feel better, or whether it’s actually a constructive thing to do.

By Tom Geraghty, edited by Jade Garratt

References and further reading:

Alicke, M.D., 2000. Culpable control and the psychology of blame. Psychological bulletin, 126(4), p.556.

Cameron, Deborah. (2014). Straight talking: The sociolinguistics of heterosexuality. Langage et société. 148. 75. 10.3917/ls.148.0075.

Cooper, D., 1997. Implementing Behavioural Measurement and Management To Maximise People’s Performance.

Cooper MD. Behavioral safety interventions: A review of process design factors. Professional Safety. 2009 February;:36–45

Dekker, S. 2002 The reinvention of human error: http://www.lusa.lu.se/upload/Trafikflyghogskolan/TR2002-01_ReInventionofHumanError.pdf

Dekker, S. (2014). The Field Guide to Understanding ‘Human Error’ (3rd ed.). CRC Press

Edmondson, A.C., 2004. Learning from failure in health care: frequent opportunities, pervasive barriers. BMJ Quality & Safety, 13(suppl 2), pp.ii3-ii9.

Guglielmo, S., Monroe, A.E. and Malle, B.F., 2009. At the heart of morality lies folk psychology. Inquiry, 52(5), pp.449-466.

Hewstone, M., 1990. The ‘ultimate attribution error’? A review of the literature on intergroup causal attribution. European journal of social psychology, 20(4), pp.311-335.

Holden, R.J., 2009. People or systems? To blame is human. The fix is to engineer. Professional safety, 54(12), p.34.

Hollnagel E, Woods DD. Joint Cognitive Systems: Foundations of Cognitive Systems Engineering. Boca Raton, FL: Taylor & Francis; 2005.

Kraut, R., 2001. Aristotle’s ethics. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford University. Available at: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/aristotle-ethics/

Lerner, M.J. and Lerner, M.J., 1980. The belief in a just world (pp. 9-30). Springer US.

Malle, B.F., Guglielmo, S. and Monroe, A.E., 2014. A theory of blame. Psychological Inquiry, 25(2), pp.147-186.

Nagel, T., 1979. Moral luck. Mortal Questions [New York: Cambridge University Press, 1979], pp.31-32.

Nelkin, D.K., 2019. Thinking outside the (traditional) boxes of moral luck. Midwest Studies in Philosophy, 43(1), pp.7-23.

Nietzsche’s On the Genealogy of Morality, translated by Carol Diethe and edited by Keith Ansell-Pearson, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994, ISBN 0-521-87123-9.

Perrow C. Normal Accidents: Living With High-Risk Technologies. New York: Basic Books; 1984.

Pettigrew, T.F., 1979. The ultimate attribution error: Extending Allport’s cognitive analysis of prejudice. Personality and social psychology bulletin, 5(4), pp.461-476.

Reason J. Human error: Models and management. British Medical Journal. 2000;320:768–770. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7237.768.

Sha, Y., Zhang, Y. and Zhang, Y., 2024. How safety accountability impacts the safety performance of safety managers: A moderated mediating model. Journal of safety research, 89, pp.160-171.

Shaver KG, Drown D. On causality, responsibility, and self-blame:A theoretical note. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;50:697–702. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.50.4.697.

Shorrock, S. 2016. Just Culture: Who Are We Really Afraid Of?, Humanistic Systems. Available at: https://humanisticsystems.com/2016/11/24/just-culture-who-are-we-really-afraid-of/

Tversky, A. and Kahneman, D., 1974. Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases: Biases in judgments reveal some heuristics of thinking under uncertainty. science, 185(4157), pp.1124-1131.

Woods DD, Cook RI. Perspectives on human error: Hindsight biases and local rationality. In: Durso FT, Nickerson RS, Schvaneveldt RW, Durnais ST, Lindsay DS, Chi MTH, editors. Handbook of Applied Cognition. New York: Wiley & Sons; 1999. pp. 141–171.

Online Psychological Safety Workshops

We’re excited to announce the next round of workshops will take place in March 2025, with two streams to choose from.

You can choose to attend one or more individual modules, or enrol on the complete Train The Trainer programme.

The Complete Psychological Safety: Train the Trainer is our flagship programme. It goes both broad and deep into the world of psychological safety, using a variety of lenses and perspectives to explore how to understand, foster, build, maintain and measure psychological safety as well as how to inspire others to work on it themselves.

The sessions are delivered via Zoom and we use Miro boards, supplemental handouts, online resources and academic papers to support learning and engagement during the sessions.

Our aim is to ensure you learn as much from the other attendees as you do from us during the session, and we work to create learning spaces in the workshops which are inclusive, accessible and psychologically safe for all. We’ve run these workshops for several years now, and each time we refine and improve them further, making sure you gain the benefit of all our previous experience and learning. Delivering these sessions is one of the most enjoyable aspects of our work, and we want to make sure you have a great time too and get the best possible value from them.

All attendees receive a Credly Badge, a certificate of completion to confirm attendance, further reading, materials and resources used in the session, a copy of the Psychological Safety Action Pack and a licence to use it in your organisation, access to a private alumni group, and some swag!

Psychological Safety in Practice

Autism at work

This is a powerful piece by Ludmila N. Praslova, a professor of organisational psychology, who is autistic. Contrary to certain stereotypes, autism doesn’t limit professional potential; systemic discrimination and exclusionary workplace norms do. People with autism can be exceptionally effective when their roles align with their strengths. Yet they face many barriers including biased hiring practices to environments that ignore or penalise their differences. We should instead reject neuronormative approaches and assumptions, and allow everyone (not just neurodiverse folks) to better craft their roles to best fit their strengths.

The Notre-Dame fire

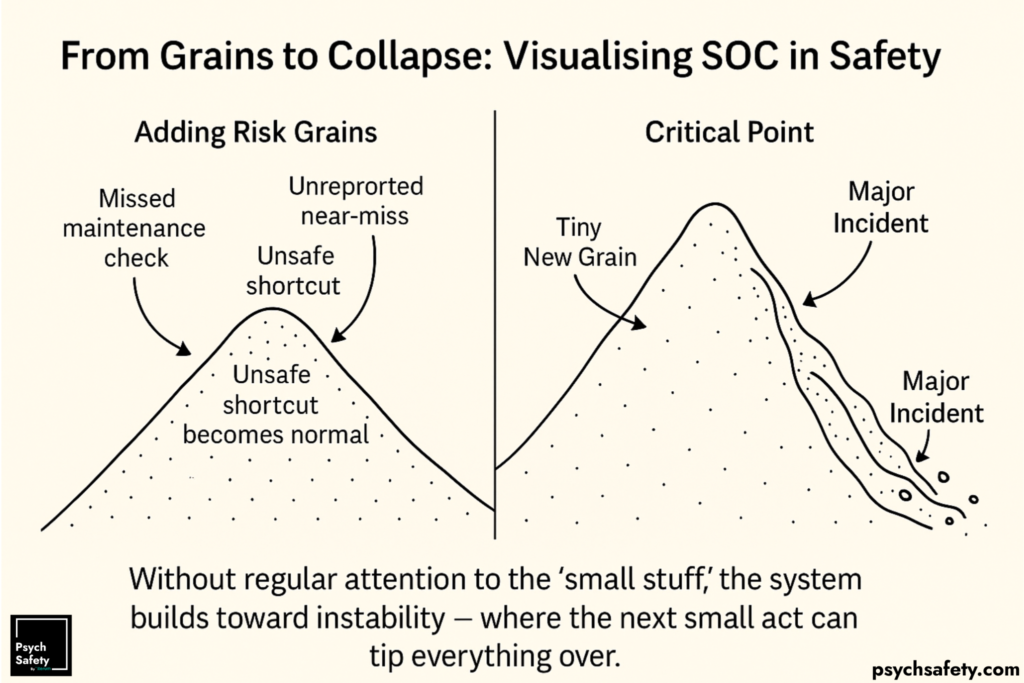

This Harvard Business School case study by Amy Edmondson and co-author Jérôme Barthelemy highlights how numerous small lapses and overlooked safeguards likely combined to create a massive, preventable disaster. Instead of a single glaring error, the tragedy exemplifies a “complex failure,” where multiple minor violations of safety rules and best practices such as workers smoking near flammable materials, poor alarm procedures, and built-in response delays compounded to produce a catastrophe reminicent of a Perrovian “Normal Accident“.

The Ghosts of Failures Past, Present and Yet to Come

This excellent piece from Steven Shorrock from 2014 uses Charles Dickens’ “A Christmas Carol” as a metaphor to examine how organisations attempt to learn from failure and why that approach often falls short. Traditionally, organisations (like Scrooge) generally learn from the “ghosts” of negative events: failures of the past, present, and those yet to come.

However, organisations and teams would be better placed to gather and consider data about everyday successes, adaptations, and routine performance, not just failures. By understanding what usually goes right, we can gain a clearer picture of the system’s functioning. This allows us to identify weak signals of failure, appreciate better how work is actually done, and make more things succeed as well as reduce the number of things going wrong.

We still have a few spaces left in our January 9th workshop on Delivering Effective Feedback – book here!

The post Blame appeared first on Psych Safety.