Déformation professionnelle

By Tom Geraghty

“Every specialist, owing to a well-known professional bias, believes that he understands the entire human being, while in reality he only grasps a tiny part of him.” Alexis Carrel, Nobel laureate

We all see the world through our own, unique, lens. That lens is shaped by the environment we grew up and live in, our experiences, education, cultural history, and so much else. Including, importantly, our jobs. There’s even a term for the effect that our profession has on how we see the world: déformation professionnelle.

The term “déformation professionnelle”, which literally translates as “professional deformation” was originally used to describe a bodily deformity caused by somebody’s occupation, such as the hunch of a shoemaker or “Phossy Jaw” (Phosphorus Necrosis of the Jaw) suffered by matchmakers who were routinely exposed to white phosphorus. In fact the first usage of the term appears in an 1887 paper by Morel-Lavallée, “Sur une fausse ‘dent d’Hutchinson’; déformation professionnelle chez un cordonnier” (“On a false ‘Hutchinson’s tooth’; professional deformation in a shoemaker.“) in the journal Annales de Dermatologie et de Syphiligraphie.

Observations of these early, physical manifestations of déformation professionnelle were precursors to the modern field of ergonomics, and spurred some of the first discussions about workplace and tooling design, seating, and posture.

Nowadays, the term déformation professionnelle is used more conceptually, to denote the way our professional training and experiences shape or even distort how we perceive problems, communicate, and behave. This more modern use of the term was introduced by Belgian sociologist Daniel Warnotte in 1937, in a piece titled ‘Bureaucratie et fonctionnarisme’ bemoaning the stifling effect of bureaucracy. More recently, in 2008, Geoffrey Pullum coined the term “nerdview” which captures the idea exceptionally well:

“…people with any kind of technical knowledge of a domain tend to get hopelessly (and unwittingly) stuck in a frame of reference that relates to their view of the issue, and their trade’s technical parlance, not that of the ordinary humans with whom they so signally [singularly?] fail to engage.”

In other words, when you have a hammer, everything looks like a nail. (I believe from Maslow, 1966)

In 1968, John Dewey described the most extreme version of déformation professionnelle as an “occupational psychosis”, when someone’s occupation or career makes them so biased that they could be described as psychotic, adopting ideas or behaviours that seem absurd or irrational to the external public.

Déformation professionnelle and Psychological Safety

Déformation professionnelle changes the way we see and conceptualise even the most simple things. Let’s take a hammer: to a carpenter: it’s a tool to build something, to a demolition worker: it’s a tool to break things, to an artist: it’s a tool of creativity.

And if this happens with something as simple as a hammer, imagine what happens when we begin to engage with more complex concepts such as psychological safety. One of the most fascinating aspects of psychological safety is that while it is well-defined in social or organisational behaviour terms – i.e., “a shared belief that a team is safe for interpersonal risk-taking” – it is viewed differently depending on a person’s professional background and the domain in which they operate. These different interpretations and perspectives aren’t right or wrong; instead, they reflect the unique priorities, fears, concerns and goals that each profession considers most important. Our different lenses mean that we often interpret the same thing in very different ways.

Let’s dive into some of those different professional lenses on psychological safety. Whilst the below are generalisations, and there will naturally be exceptions, they are broadly representative of the domains.

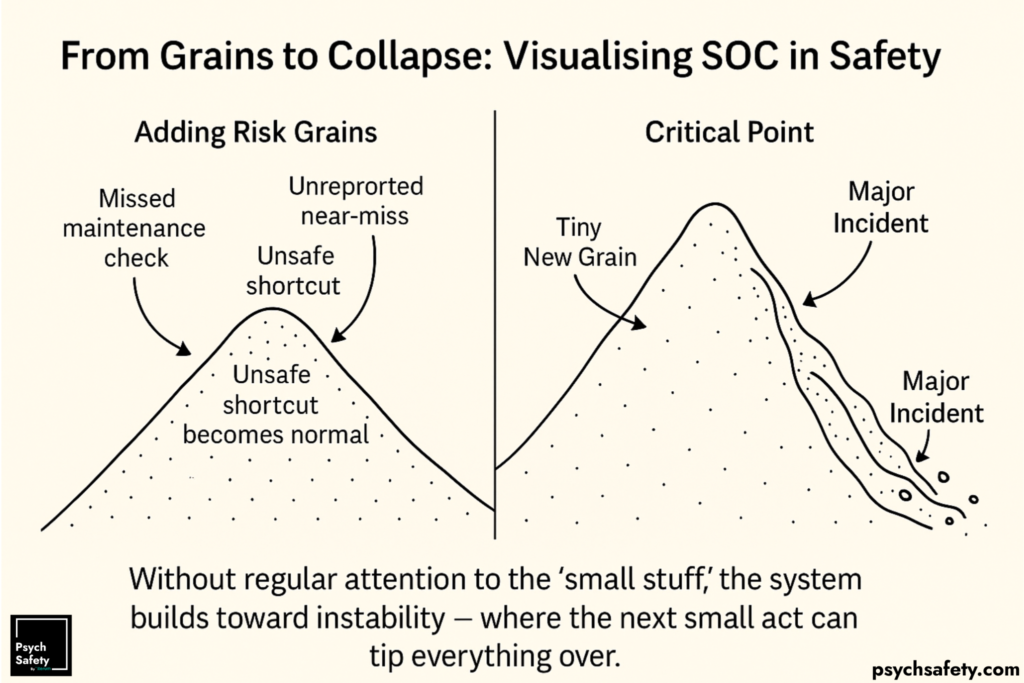

- Safety: Psychological safety is viewed as preventing harm by ensuring that people feel able to raise concerns before incidents occur and report mistakes or incidents without fear. This supports learning and compliance with safety practices, ultimately preventing and mitigating further incidents. The safety professional’s primary motivation is reducing physical harm, so they will naturally think about psychological safety as a mechanism that facilitates hazard identification, compliance with safety practices, and learning from failures.

- Healthcare: Recognising that a great proportion of patient safety incidents arise from communication breakdowns, psychological safety is seen as key to improving clear and prompt communication, enabling error reporting without fear of repercussions, and ensuring seamless teamwork in fast-changing clinical and surgical contexts.

- Technology & Product Development: Psychological safety may be viewed primarily as an enabler for innovation through encouraging open idea-sharing, faster problem-solving, and the ability to admit mistakes. This leads to more rapid development cycles, shorter time-to-market, and more reliable and resilient systems.

- Manufacturing: In a field focused primarily on quality, efficiency and reducing waste, psychological safety is often considered crucial in catching defects early, preventing costly downstream failures; akin to the Andon Cord principle of empowering frontline workers to pause the line when issues arise.

- People, HR, Wellbeing & DEI: Often viewed through the lens of engagement, wellbeing, and inclusion, psychological safety can be seen as the foundation for employee authenticity, retention, and health. It may also be less about focusing solely on the positive business outcomes of increased psychological safety and more about a deeper belief that creating psychological safety is fundamentally the right thing to do. And they’re right too.

- Senior Leadership: Psychological safety is considered crucial to prevent disasters and facilitate organisational performance, resilience, and adaptability. Folks in senior leadership positions may view psychological safety as necessary to ensure that critical information (particularly when it’s bad news) is passed to decision makers, and a way to navigate a VUCA (Volatile, Uncertain, Complex and Ambiguous) world.

So why does déformation professionnelle matter?

In itself, it’s not necessarily a problem, and it’s quite inevitable that the profession we are in will shape our worldview. However, where it begins to cause issues around working on psychological safety is where we’re not adequately tuned into the breadth of reasons for working on psychological safety, or where we’re not talking the ‘same language’. This is not even unique to those working in industry. Even professors and academics can fall into the déformation professionnelle trap by making incorrect assumptions about why psychological safety is a positive thing to do, which leads to misleading research conclusions.

And while the examples above are broad generalisations, they highlight how we all tend to view psychological safety through the lens of our own work, even in subtle ways. This brings us to two key takeaways around the value of recognising and acknowledging our own deformation professionelle:

- We begin to see our challenges through different frames of reference and find solutions we wouldn’t have thought of. Surfacing our own biases is very, very hard to do, but we can start by broadening our exposure to different ideas and perspectives, inviting conversation with others who have different backgrounds, skills, and experiences and applying humble inquiry.

- We can ensure we are speaking in the right terms and are on the same wavelength as others when attempting to reach a consensus or establish shared foundations. It’s no good attempting to enthuse a safety professional about how psychological safety helps teams innovate faster, and it’s not much help to evangelise to a product owner about how psychological safety helps reduce workplace accidents.

Building a Shared Language

Depending on our field – whether it’s safety, healthcare, tech, manufacturing, people or something else – psychological safety might appear to be primarily about reducing harm, improving quality, driving innovation or enhancing wellbeing. And all of these perspectives are valid.

By recognising déformation professionnelle, and acknowledging that we see the world in different ways and value different things, we can build bridges between domains and start to create a shared language. This is crucial for getting buy-in for psychological safety initiatives, since we know that psychological safety itself is rarely the goal. We need to be talking about what ultimately matters to people, whether that’s developing the next world-changing product or keeping people safe from harm.

Further reading:

Can workplaces have too much psychological safety?

Déformation Professionnelle: How Profession Distorts Perspective. Steven Shorrock

Warnotte, D. (1937). Bureaucratie et fonctionnarisme. Revue de l’Institut de Sociologie, 17: 245-260.

Merton, Robert, Social Theory and Social Structure, Simon & Schuster, 1968, p. 252.

Man, The Unknown. By Alexis Carrell, 1935

Open Enrolment Online Workshops

Booking now for 10th – 27th March 2025

Looking to deepen your expertise in psychological safety—whether for your team, your organisation, or your own practice? Our flagship Complete Psychological Safety Course: Train the Trainer is designed for leaders, trainers, and consultants who want to create safer, more effective workplaces.

This flexible programme consists of six interactive 2.5-hour online workshops, each offering a different lens on how to understand, foster, build, maintain, and measure psychological safety—as well as how to inspire others to do the same. You can join individual sessions relevant to your role or take the full programme to gain a comprehensive Train the Trainer package.

Whether you’re:

- A leader or manager looking to foster a high-performing, open culture in your organisation,

- A team member wanting to integrate psychological safety into all aspects of your work

- An internal trainer or facilitator developing teams and embedding psychological safety across your workplace, or

- An independent coach or consultant wanting to deliver psychological safety training for your own clients,

… this programme gives you the practical tools, expert guidance, and real-world applications to make an impact.

Secure your spot today and start building psychologically safer, more inclusive spaces for meaningful work.

All our workshops provide certificated CPD hours and Credly badges to evidence your professional development.

Psychological Safety in Practice

Neurodiversity-affirming practices

This excellent piece from Autistic Realms advocates for a shift toward neurodiversity-affirming practices in educational (and other) contexts. It does a great job of highlighting common barriers that perpetuate exclusion and harm for neurodivergent students (such as Autistic and ADHD learners) and offers ways to create environments in which all learners can thrive. Central to the argument is the recognition that standard, one-size-fits-all approaches (and the biases that maintain them) should give way to inclusive, flexible, and strengths-based approaches.

Psychological Accessibility

In this great follow-up piece from our own Navya Adhikarla, she introduces the concept of psychological accessibility – the bridge between two traditionally separate workplace priorities: (1) physical and digital accessibility and (2) psychological safety. Drawing on her experiences as a neurodivergent, disabled professional, Navya argues that while accessibility and psychological safety are typically discussed independently, they mutually reinforce each other.

Radiation oncology at crossroads: Rise of AI and managing the unexpected

Here’s a good letter from Mohammad Bakhtiari in the Journal of Applied Clinical Medical Physics: as artificial intelligence takes on a larger role in radiation oncology, it can improve efficiency, but also add complexity and potential for new types of failure. Drawing lessons from aviation safety, Bakhtiari proposes a three-step approach: pre-planning (using checklists and risk assessments), being adaptable on treatment day (with psychological safety, clear communication and collective problem-solving), and intentional learning through debriefings and incident reviews. This human-centered method relies on psychological safety, diverse perspectives, and emotional intelligence to handle the complexities introduced by new tools effectively while keeping patients safe.

301er link sharing tool

Finally, I thought I’d share this little link sharing tool that I created: 301er.io

With recent increasing concerns over access to knowledge and services in the US and elsewhere, I wanted to create a tool that allows you to share a link to someone (for example, a website on access to reproductive healthcare), and once used, will then go to some other, innocuous destination such as a local cafe. You can create a link, define how long it lasts for (number of clicks or for a duration), and define where the link goes to afterwards. If you suspect someone is checking or intercepting your messages, you can also enter an email address that will receive an email when the link is clicked.

Currently very much in beta release! None of the information is stored for longer than is necessary, and is encrypted in transit and at rest.

The post Déformation professionnelle appeared first on Psych Safety.