Efficiency vs Resilience

By Tom Geraghty

Standardisation is often used as a way to increase organisational efficiency and scalability. Through reducing variation, we can standardise our tools, training, processes and more, enabling us to optimise systems and better achieve our desired outcomes. However, there’s an important corollary that’s often overlooked: what are we potentially sacrificing in the name of efficiency and standardisation? What happens to organisational resilience when we focus too much on ruthless standardisation and efficiency?

Just as there’s a tradeoff between efficiency and thoroughness, there can be a tension, or tradeoff, between efficiency and resilience. Managers and leaders are often praised and rewarded for increasing efficiency, in part because it’s so much easier to measure efficiency than resilience. In this piece, I’ll use an example from farming to explore this tension.

What do we mean by resilience? In this case, we’re talking about the capacity to anticipate, detect, respond to and learn from change. It’s not about being tough and “robust”, like a brick wall is robust, but instead about being resilient through the capacity to respond, recover and bounce back stronger, much like a community or a family adapts when things take us by surprise.

In farming, we know that large, standardised, uniform monocultures are highly efficient. We can buy seed, fertiliser and treatment in large batches, we can use large machines to cultivate and harvest it quickly at relatively low cost, and we can sell and transport the crop in bulk.

The Cost of Efficiency

But what’s the cost of this standardisation and efficiency? And can this be sustainable?

As in many other domains, monocultures in farming are risky, sometimes even deadly. Plant a large field with the same crop year after year, and eventually, no matter how much care you take to fertilise it, protect it from pests, and shield it from diseases and natural environmental impacts, it’ll fail. Maybe catastrophically.

And industrialised monocultures are far from the only farming method. Just a few hundred years ago, much land in England (and in Scotland and Wales too) was “common land” – land that us “commoners” have the right to use. An open field practice called strip farming was often employed to manage shared agricultural land. Every local family, “by reason of vicinage” (being local and contributing to the health and subsistence of the community), was provided a strip of land a furlong (a “furrow-long”) in length (about 200 metres), and about 5-20 metres wide, on which to grow crops. The more members of the family, the more land they were provided with [Footnote 1]. To rear livestock, everyone had access to shared common land, where each family was allowed to graze a certain number of various kinds of livestock on the land [Footnote 2].

Despite the fact that enclosure (mainly between 1604 and 1914) took the vast majority of this common land into the hands of aristocratic landowners (around 6.8 million acres, over a fifth of the land in England), you can still see many of these ancient ridge and furrow systems today. Look out across many old pastures in England and they look sort of corrugated: the ridge occurring as the farmers ploughed the strips up and down in a clockwise fashion, the mouldboard moving soil towards the centre of the ridge.

The strips were provided across different areas around the village: some on high ground, some on low, on different types of soil, different aspects, etc. Although this might seem inefficient – it meant carrying tools and crops to and from different places – it provided resilience against threats such as crop disease or flooding. Something that affected one area most probably wouldn’t affect another elsewhere, protecting the families from complete devastation as a result of a single event.

People cropping adjacent strips would also usually be growing different things at different times. One family may be growing potatoes whilst their immediate neighbours are growing oats and beans. Thus, if blight, a potato disease, struck one area, it would need to traverse multiple spatial boundaries of other non-potato crops before it could affect the potatoes grown in a nearby strip. Prevailing wind, humidity, and growing different cultivars all play a role in transmission, but simple physical distance is still one of the best ways to prevent a disease from spreading rapidly and devastatingly.

Efficiency, Standardisation and Scale

Nowadays, we tend to prioritise efficiency and standardisation for scale, instead of using less efficient strip farming methods, and growers spray their increasingly large fields planted only with (for example) potatoes with fungicide multiple times during the season as a preventative measure, especially during a Smith Period (when it’s mild and humid and potato blight is most common). But still, sometimes, whole crops fail. The Irish Potato Famine (The Great Hunger) is a classic example of the devastating impact of this scale of failure [Footnote 3].

Another contemporary example of the vulnerability of monocultures is Fusarium wilt of bananas (also known as Panama disease). In the 1950s this nearly wiped out banana crops worldwide because we relied almost exclusively upon a single cultivar – the Gros Michel – which was vulnerable to Fusarium wilt. We now rely primarily on the Cavendish cultivar of bananas, which have increased resistance to Fusarium, and if you ever hear anyone say that “bananas don’t taste as good as they used to,” that’s true. The Gros Michel cultivar was considered much tastier than the Cavendish. However, even the Cavendish is now under threat: from a new strain of Fusarium oxysporum impacting parts of Asia and spreading elsewhere, so expect a banana crisis soon. Banana agriculture is still not particularly resilient…

Let’s think about our organisations. Where are we trading resilience for efficiency? Where are we rewarding ever higher utilisation and cost-effectiveness, over long-term sustainability? What happens if the market changes rapidly? What if there’s a global event such as a pandemic, or a different global shock that we cannot predict? Where is our resilience, our diversity, our capacity for anticipating and adapting to change?

There’s a risk with organisations that we trim them so much to the bone, making them so ruthlessly efficient and lean, and so highly tuned to our current economic and consumer state that we’re vulnerable to a catastrophic failure that we simply didn’t see coming. The story of Nokia is well used for good reason in this respect. When we’re finely attuned and adapted to our current environment and context, we’re especially vulnerable to economic, environmental or political changes.

Diversity as Strength

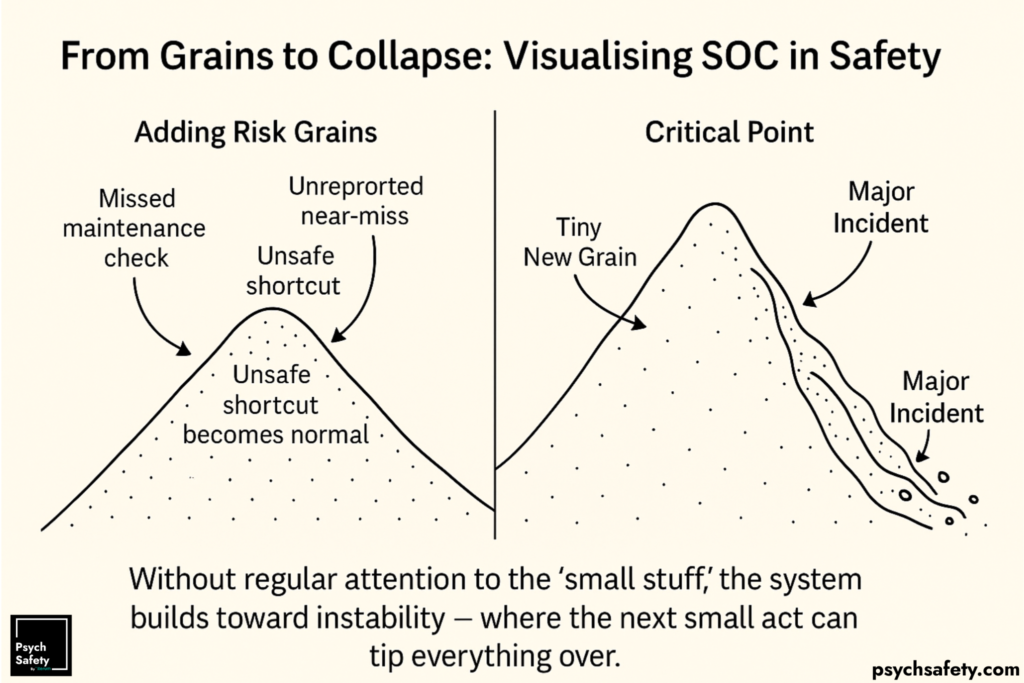

Diversity is a strength at every scale. Diverse teams, diverse organisations, diverse strategies, and diverse marketplaces are always more resilient than monocultures. Ashby’s Law of Requisite Variety states that complex problems require a level of diversity in approaches or views that matches the level of complexity. Yet the presence of diversity alone isn’t enough: people must also feel safe sharing their diverse perspectives.

That’s one reason why psychological safety matters for organisational resilience. This need for diversity is also why governments intervene when organisations begin to become monopolies – not because it’s unfair, but because it’s dangerous. Monopolies make economies vulnerable. The existence of diversity, slack and buffer capacity within organisations provides the resilience and strength to meet an uncertain and volatile future. Resilience spreads our risks, gives us options, and even allows us to capitalise on change. And adaptability – the ability to pivot or repurpose resources when conditions change – can be a great competitive advantage, not just a defensive strategy.

Satisficing for Resilience

There is, of course, a vast spectrum, as well as a tension, between the two extremes of resilience and efficiency. Most of us may not have or can’t afford the luxury of maintaining a great deal of slack in our organisational systems. The trick is finding the balance. This is what Herbert Simon termed “satisficing” – a heuristic of “satisfy” and “suffice” that finds the balance between two competing demands. A satisficing strategy in this case may be to ‘build in enough resilience to anticipate, adapt to, and learn from plausible crises.’ Of course, that satisfice balance point will be constantly shifting too: just like any healthy ecosystem, a healthy organisation is in a state of perpetual flux.

“When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the Universe.”

John Muir, My First Summer in the Sierra

Footnotes:

1: In Scotland, a similar practice was known as “runrig”, and interestingly the rigs were periodically reassigned so that no single family had continuous use of the best or worst land.

2: Hardin’s famous essay “The Tragedy of the Commons” doesn’t actually reflect the commons in practice. It has been widely critiqued as overly simplistic and not accounting for community norms and governance, and potentially racist. It is perfectly possible to fairly, sustainably and efficiently share resources amongst a community, as Nobel prize winner Elinor Ostrom has shown.

3: The proximate cause of the Irish Potato Famine was potato blight (Phytophthora infestans) but was made far worse due to the British Government endorsing large amounts of food being exported from Ireland to England during the famine.

Further reading:

van Staveren, I., 2023. The Paradox of Resilience and Efficiency. Journal of Economic Issues, 57(3), pp.808-813.

Markolf, S.A., Helmrich, A., Kim, Y., Hoff, R. and Chester, M., 2022. Balancing efficiency and resilience objectives in pursuit of sustainable infrastructure transformations. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 56, p.101181.

Critique of The Tragedy of the Commons: https://discardstudies.com/2019/07/15/the-tragedy-of-the-tragedy-of-the-commons/

Elinor Ostrom’s 8 rules for managing the commons: https://earthbound.report/2018/01/15/elinor-ostroms-8-rules-for-managing-the-commons/

ETTO: https://erikhollnagel.com/ideas/etto-principle/

Utilisation, slack, and resilience: https://psychsafety.com/queueing-theory-slack-and-resilience/

The fall of Nokia: https://knowledge.insead.edu/strategy/strategic-decisions-caused-nokias-failure

Klir, G.J. and Ashby, W.R., 1991. Requisite variety and its implications for the control of complex systems. Facets of systems science, pp.405-417. http://pcp.vub.ac.be/books/AshbyReqVar.pdf

This week’s poem:

Extract from The Mores, by John Clare

Each little tyrant with his little sign

Shows where man claims earth glows no more divine

But paths to freedom and to childhood dear

A board sticks up to notice ‘no road here’

And on the tree with ivy overhung

The hated sign by vulgar taste is hung

As tho’ the very birds should learn to know

When they go there they must no further go

Thus, with the poor, scared freedom bade goodbye

And much they feel it in the smothered sigh

And birds and trees and flowers without a name

All sighed when lawless law’s enclosure came

And dreams of plunder in such rebel schemes

Have found too truly that they were but dreams.

Psychological Safety in Practice

Eye contact

This paper from 2015 by Shota Uono and Jari K Hietanen examined how eye contact is perceived among Finnish and Japanese individuals. They found that Finnish participants were more accurate at distinguishing direct from slightly averted gazes with culturally familiar faces, possibly due to a cultural norm of frequent, sustained eye contact. Japanese participants, however, did not show this difference, possibly because direct eye contact is less common and often culturally discouraged in Japan.

When we’re thinking about psychological safety, these findings help to highlight the importance of being mindful of different cultural expectations around eye contact, otherwise we risk misinterpreting different degrees of eye contact and perceive people to be more or less psychologically safe, when it’s not the case.

RaDonda Vaught

We often refer to the case of RaDonda Vaught in our workshops, who was found guilty of criminally negligent homicide after accidentally killing a patient by incorrectly administering vecuronium, instead of midazolam as ordered. This is a great article in the British Journal of Anaesthesia, reflecting on the case and the fallout from it: “RaDonda Vaught did not come to work that day to deliberately contribute to Charlene Murphy’s death, but was set up to fail by a system that allowed a fatal mistake to happen.” The conviction of Vaught as a result of this case has made patients less safe, not more.

‘I do not work in a vacuum. I work in a healthcare system.’ RaDonda Vaught

The post Efficiency versus Resilience appeared first on Psych Safety.