Addressing Power through “Flattening” Organisations

Steep power gradients are one of the most significant factors that contribute to reducing psychological safety. These steep differentials in perceived power have contributed to many disasters including the Tenerife Airport disaster in 1977, Chernobyl, the Challenger Space Shuttle, and numerous others. This is why reducing power gradients is number 1 in our top ten ways to build psychological safety. There are many different things we can do in order to reduce that gradient, from very simple practices like introducing ourselves by our given names instead of our job title, rank, or level, all the way through to overhauling our organisational structure.

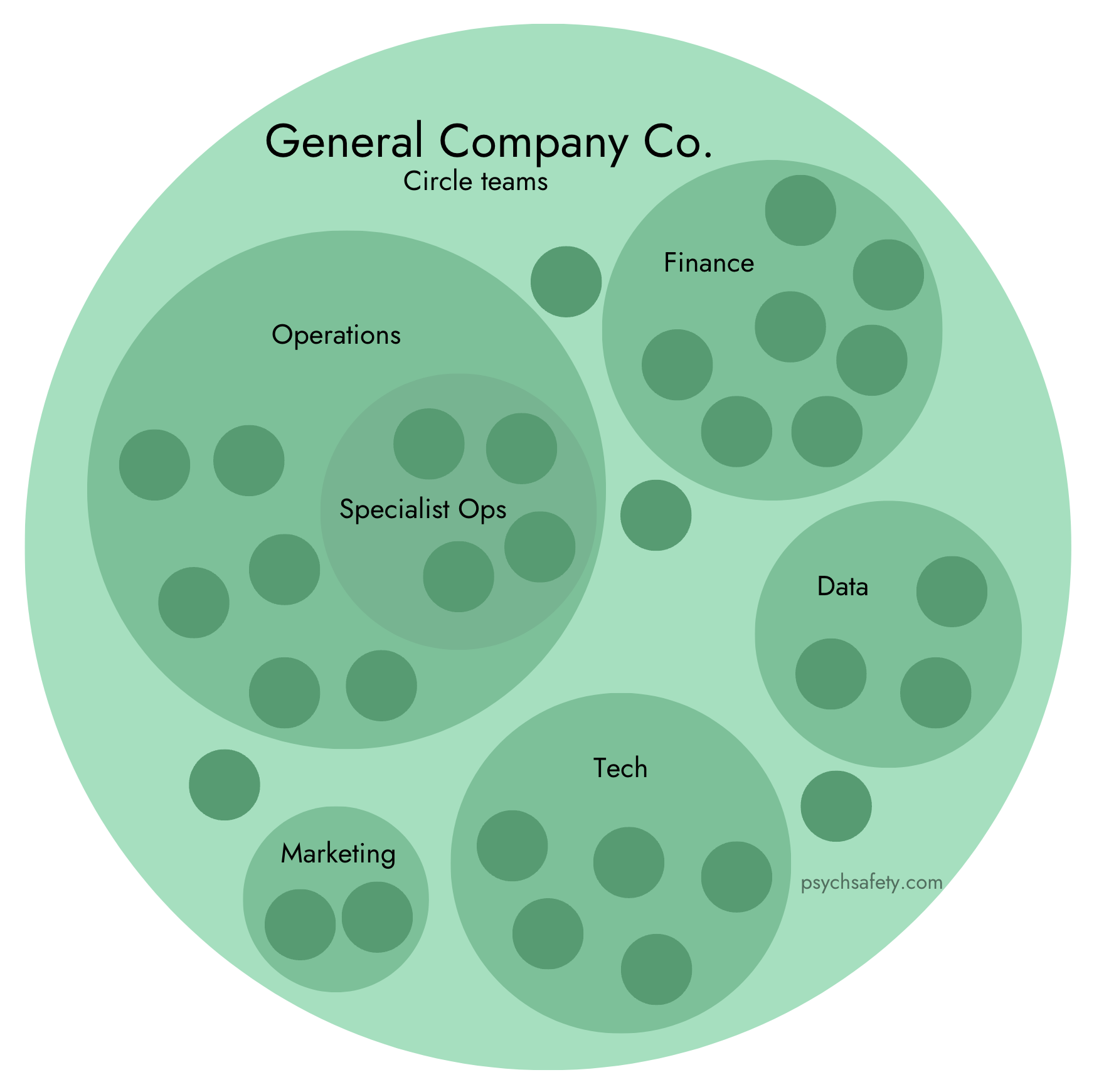

One of those more radical approaches is the idea of transitioning to some form of “flattened” organisational hierarchy or structure. And one of those models is “holacracy”. Holacracy involves simplifying and “flattening” hierarchies via (amongst other things) adopting “circle teams” and at a basic level, it exchanges formal structure for rules. It was developed by software engineer Brian Robertson, and leans heavily on ideas from software, such as API’s, formal principles, and rules. The aims of holacracy are to better distribute power throughout the organisation via approaches like self organising teams, different meeting formats, greater team autonomy, and devolved decision making processes. Other similar concepts include “Sociocracy“, Teal Organisations, or approaches that combine some or all of these ideas together. In this article, we’re primarily referring to holacracy, but the same principles apply to most organisational “flattening” approaches.

This can, when done well, bring some real advantages. For instance, teams may experience a reduction in the inefficiencies and the bureaucratic burden of very hierarchical structures. Some also report that it helps to break down silos and improve collaboration within and between teams. However, holacracy primarily focuses on the first typology of power – formal power imbued by position and hierarchy within an organisation. And this isn’t the whole story of how power actually manifests and flows in an organisation.

Organisational power flows

We can think of an organisation as a system that at a certain point in time contains a certain, finite amount of power. This power takes different forms, exists in different places and flows in certain ways, just like money does in an organisation. When we restructure, for example by flattening an organisation (assuming we don’t reduce the number of people) we don’t reduce the total amount of power that resides within it. What restructuring will certainly do though is change the types of power, move it around and influence how it flows. This may not always result in more inclusive, equitable arrangements, and there’s a risk that it actually leads to less equitable outcomes. Transitions towards holacratic organisations sometimes find that “shadow hierarchies” emerge, which can be more harmful than formal, explicit hierarchies in large part because they’re invisible.

“…structurelessness becomes a way of masking power, and …is usually most strongly advocated by those who are the most powerful (whether they are conscious of their power or not).”

Jo Freeman, American political scientist and feminist,1971

Without the overt structures and scaffolds that exist within formal hierarchies, in flattened organisations we may find it much more difficult to influence where that power flows and accumulates.

Positional or formal power tends to be more visible than many types of informal power. If our approach to “flattening” the power gradients is done carelessly, recklessly or without regard for informal power, we may find we’ve exchanged the visible, formal, positional power typology for invisible, informal power of status, expert, and demography. The informal power was always there, of course, but it was to an extent mitigated and constrained by the structures and hierarchies of positional, formal power.

This isn’t to say that hierarchical power is any “better” than informal power. It isn’t a value statement. No type of power is necessarily good or bad – they just are: what matters is what we do with power. Overly rigid, bureaucratic, command-control, power-over hierarchies are generally bad for people and for organisations, and an absence of any formal structure can also be bad for people and for organisations. As Richard Bartlett writes, hierarchies are not necessarily bad – “Focusing on “hierarchy” doesn’t just miss the point, it creates cover for extremely toxic behaviour.”

Structure, power and psychological safety

An example of where a lack of hierarchical decision-making and structure can present challenges is the often-cited example of having people in an organisation self-determine their salaries. Although at face value, this might appear to be very empowering and liberating, we know of no organisation that in practice implements self-determined salaries without a lot of checks and balances. Perhaps more than the risk of people over-paying themselves is the risk that those from historically marginalised groups may be less likely to ask for as much or effectively advocate for themselves. To request a salary for ourselves is to take a large interpersonal risk, so we’re unlikely to ask for more money if we don’t already feel psychologically safe or we have less of a socioeconomic safety net should it backfire. In practice, we recognise that organisations need structures in place to mitigate for those who are less likely or less able to advocate for themselves.

And this speaks to another challenge when it comes to psychological safety. As we’ve seen, “flattening” an organisation doesn’t always reduce the burden of speaking up against power gradients – sometimes it simply exchanges the burden of one overt power gradient for another, more covert one. This may well negatively impact the very people who already suffer the most from oppressive structures and power gradients in an organisation.

Power begets power. During any change, particularly a change in organisational structure, power tends to flow towards those with greater informal power to begin with, since they are better positioned to take advantage of the change, whether intentionally or not. This doesn’t make them bad people – far from it: this is a function of power itself, not people.

Thoughtful, intelligent approaches to structure

And it’s certainly not inevitable that organisational “flattening” efforts such as holacracy fail: many flattening or “flattish” transformations demonstrate at least some success. But they aren’t straightforward, and they require intelligent and careful approaches that adapt to the circumstances and continually reflect on and learn from what emerges through the process. Most importantly, we mustn’t be beholden to a single dogmatic way of doing things: if it turns out that the approach we thought would work actually doesn’t in practice, or even makes things worse, we need to possess the humility to stop, re-examine why we’re doing it in the first place, and change our approach.

A question we can ask ourselves is how can we make changes to better provide power to, and power for, people in our organisations? Sometimes that may include redesigning the organisation itself, but there are other, arguably easier, ways too. And we should remember that hierarchy isn’t inherently a bad thing. It can, if used to provide power to, rather than power over, be a force for good.

Further Reading:

Typologies of Power

Power and Mary Parker Follett

Top 10 Ways to Foster Psychological Safety in the Workplace

A team is only as safe as the least safe person

Psychological safety should support DEI, not replace it.

Social contracts

Psychological Safety Practices

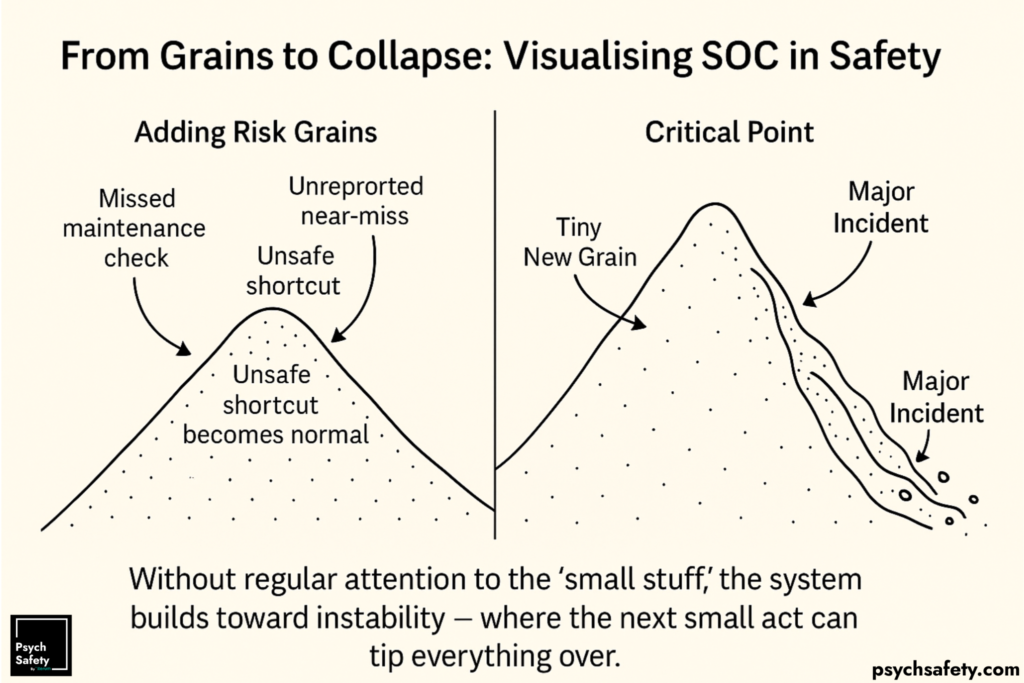

Normalisation of Deviance

Tenerife 1977

Chernobyl

Broxtowe Community Projects Food and Nappy Bank

As you may know, we donate at least £50 of the income we receive from Action Pack downloads to Broxtowe Community Projects (BCP), a community food and nappy bank helping to alleviate food and fuel poverty and social isolation across Broxtowe. They are a self referral food bank, which means they don’t ask questions and don’t require people to complete lengthy forms.

Unfortunately, the number of people facing deprivation and poverty has increased over the winter, and BCP are unable to fully meet current demand. We’ve made an extra donation, and if you feel able to do so as well, it would be incredible. Just £15 can cover the household needs for a family for a month.

Another new sticker! We had a request for Japanese language Psychological Safety stickers, so here they are!

Psychological safety full online course: March 2025

Our online psychological safety workshops cover everything from what psychological safety is to how to measure and build it in organisations. We offer a range of options to suit your needs, from foundational to advanced learning, for everyone from team members, senior leaders, consultants and trainers. All are highly engaging, inclusive and interactive learning experiences.

The workshops will help you to:

- Understand the theory and evidence for psychological safety in relation to team performance.

- Learn key practices for improving and maintaining psychological safety.

- Find out how to measure psychological safety across your organisation or within teams.

- Learn how to foster psychological safety in your teams, organisations, or your own clients.

- Ignite your leadership and management teams with the benefits of psychological safety.

- Use and apply the Psychological Safety Action Pack with teams to measure, build and maintain psychological safety

- Deliver your own workshops and training sessions with tools and techniques gleaned from our experience running training sessions over the past few years.

All our training options and workshops provide certificated CPD hours and Credly badges to evidence your professional development.

Psychological Safety in Practice

The Being Better, Together podcast

The Being Better, Together podcast is a collaboration between Learning from Excellence and Civility Saves Lives. In this episode, they’re joined by Dr Neil Spenceley, a paediatric intensivist in Glasgow. The conversation gets into some fab topics including safety-II, understanding complexity, challenges in safety investigations, reductionism, the problem with aiming for “zero”, WAD vs WAI and a LOT more. Worth a listen!

Is the camel effect the new cobra effect?

In Rajasthan, a 2015 law intended to protect camels by banning their transport and slaughter has inadvertently triggered a collapse in the camel market, echoing the “cobra effect,” in which a measure to reduce cobras actually led to more cobras in the wild. By effectively criminalising camel sales, the legislation eliminated many of the incentives to rear them, thereby hastening the very decline it aimed to prevent. The camel population has continued to decrease, and experts fear a future where they may vanish entirely or survive only in zoos. This case illustrates how policies enacted without fully considering social and economic realities can, paradoxically, produce the opposite of their intended outcomes.

“Success Cause Analysis” (SCA)

“Success Cause Analysis” (SCA) is an approach that adapts root cause analysis (RCA) methods to examine positive patient safety outcomes rather than adverse events. The authors of this paper provide a hypothetical example of how a life-threatening anaesthetic reaction was handled effectively in an outpatient clinic, leading to a good outcome. By using a structured methodology similar to RCA (fact-finding, flow diagramming, and causal statements), SCA identifies specific factors that led to success.

I would say that SCA fits within the broader “Safety-II” concept, which focuses on understanding how human adaptability and system attributes produce favourable results in complex environments. However, this example of SCA is possibly a little bit linear and reductive: the real world is non-linear, complex and ultimately, messy. I therefore wonder if the process of SCA (the conversations and the relationships that are fostered through it) may be more valuable than the actual output.

Thanks (again!) to Jonathan Cohen for the share.

Psychological safety and road safety

I was honoured to be asked to speak last year at the National Highways Road Safety conference, and here is a write up of a conversation I had with Mark Cartwright, Head of Commercial Vehicle Incident Prevention at National Highways, about the importance of psychological safety to road safety.

Why is everyone so quiet?

The post Flat Organisations, Hierarchy and Power appeared first on Psych Safety.