The Speaking up Myth

By Jade Garratt

In the world of psychological safety, we focus a lot, maybe even too much, on the speaking up side of the equation. How do we make sure people speak up with their ideas, questions, concerns and mistakes?

But this puts the onus on others to do the speaking up, and undervalues the role we play in effectively listening.

Because the crux of psychological safety is that it’s less about what people say and more about how their words are received, and how they predict they will be received. In other words, it doesn’t matter how many times you tell people to speak up, if the way you respond, the way you have responded in the past, or the way they predict you will respond is by punishing, blaming or humiliating.

And note, words like ‘punishment’ and ‘humiliation’ are quite strong, and tend to bring to mind something overt and extreme, like being yelled at or hauled into a disciplinary meeting. That’s not necessarily the case. The ‘punishment’ we fear might be something far subtler but sometimes just as scary – perhaps disapproval that leads to being overlooked for future opportunities, reputational damage or social ostracisation within the team.

This can be hard to accept. It can feel particularly frustrating if the people in our teams are reluctant to speak up for reasons unrelated to our behaviour, but because of ways they have been treated in the past. This is why psychological safety matters so much – the way we act now with our team members, our colleagues and even our friends and families will have ripple effects and repercussions well beyond our interactions with them in the moment.

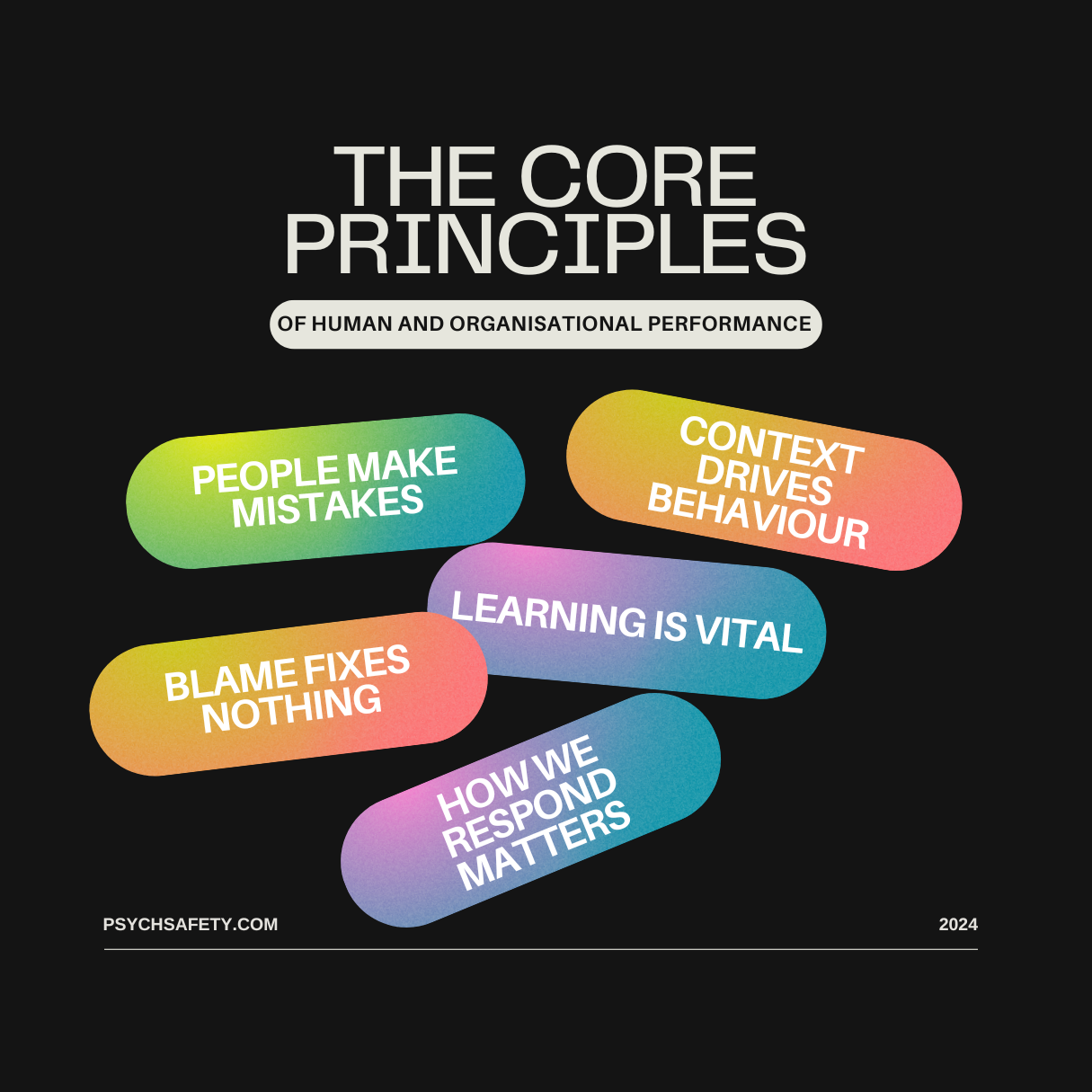

What we can do is recognise the crucial role we play in supporting others to speak up now and in the future, with us and others. In the language of Human and Organizational Performance, how we respond matters.

Managing our Responses

It’s easy to assume that you’re doing this already. Easy to think, I’m a decent person, a good leader, an approachable colleague, of course people will feel safe speaking up when I’m around. But how do we really know that?

How many of us can say, hand on heart, that we have never fired off a snappy email in frustration? Have never shown our irritation when someone asks a question that they “should” know the answer to by now? Have never been passive aggressive (or aggressive aggressive) when someone criticises our approach? It’s our reactions in these moments, when we might be tired, distracted or overwhelmed, that matter just as much as how we respond “on a good day.”

Photo by Yan Krukau

There are other times when we just misjudge how we come across. Maybe that email you sent in a hurry was intended to be concise and direct, but came across to the recipient as curt. And there are even more hidden aspects to this too – how confident can we be that the ways we respond to each other are not influenced by preconceptions, stereotypes and unconscious biases?

None of us can guarantee that we never make mistakes, or never communicate badly. We all also carry unconscious biases and preconceptions that shape how we interact. Even with the best of intentions, we will still, sometimes at least, get it wrong. But we can be sure that if we’re not looking after ourselves and our emotions, and developing more awareness of our triggers, our behaviours and their impact, then we’re likely to mess up a lot more.

Doing the Work

“The process of becoming a leader is similar, if not identical, to becoming a fully integrated human being.” – Warren Bennis

The thing about building psychological safety, and the thing about becoming a great colleague, leader and human being, is it’s an ongoing process. We are never “done”.

It means reflecting on our behaviours, asking for feedback as to how we’ve affected others and listening to it. It means working on our communication so that our impact is as close as possible to our intention. It means learning to take a breath when we hear something unexpected or unwelcome, and managing our response so that we’re not shutting down future opportunities to hear someone’s voice.

The words of Viktor Frankl, psychiatrist and Holocaust survivor, are a powerful reminder of this: “Between stimulus and response, there is a space. In that space is our power to choose our response. In our response lies our growth and our freedom.”

We don’t need to be perfect, but we do need to be humble, apologise when we mess up, and commit to doing better next time. We’ll never build psychological safety if we’re not willing to do some work on ourselves too.

Related Reading:

Human and Organisational Performance

The Seven Deadly Sins of Psychological Safety

Being Approachable

Leadership and Management

Edgar Schein’s Humble Inquiry

Hard to Say I’m Sorry

Why Should We Create Psychologically Safe Workplaces?

Non-Violent Communication (or “Giraffe Language”)

Edgar Schein’s Three Layers of Organisational Culture

Top 10 Ways to Foster Psychological Safety in the Workplace

Open Enrolment Online Workshops

Booking now for 10th – 27th March 2025

Looking to deepen your expertise in psychological safety—whether for your team, your organisation, or your own practice? Our flagship Complete Psychological Safety Course: Train the Trainer is designed for leaders, trainers, and consultants who want to create safer, more effective workplaces.

This flexible programme consists of six interactive 2.5-hour online workshops, each offering a different lens on how to understand, foster, build, maintain, and measure psychological safety—as well as how to inspire others to do the same. You can join individual sessions relevant to your role or take the full programme to gain a comprehensive Train the Trainer package.

Whether you’re:

- A leader or manager looking to foster a high-performing, open culture in your organisation,

- A team member wanting to integrate psychological safety into all aspects of your work

- An internal trainer or facilitator developing teams and embedding psychological safety across your workplace, or

- An independent coach or consultant wanting to deliver psychological safety training for your own clients,

… this programme gives you the practical tools, expert guidance, and real-world applications to make an impact.

Secure your spot today and start building psychologically safer, more inclusive spaces for meaningful work.

All our workshops provide certificated CPD hours and Credly badges to evidence your professional development.

Psychological Safety in Practice

Hindsight Magazine

Issue 36 of HindSight is out now, and worth a read. HindSight covers human and organisational factors in operations, in aviation, maritime, rail, healthcare and elsewhere. There are some great articles in here from a wide range of folks, and I wanted to draw out this quote from Alex Bristol, CEO of Skyguide, which sadly has increased relevance after yesterday’s crash in Washington.

“Safety-critical roles depend not only on the quality of the tools but also on the communication among teams and in the organisation. We rely on both formal and informal channels to keep everyone aware of the current state of operations. It’s essential that controllers and engineers feel safe to report issues, trusting that their voices will be heard.”

The SAFE Leader Podcast

Thanks so much to Mark McBride-Wright for inviting me onto the SAFE Leader podcast to talk about making psychological safety practices accessible globally, not just in wealthy countries. We also talked about the need for more research and application of psychological safety in non-western, non-white collar, more diverse contexts.

Work as imagined vs Work as Done

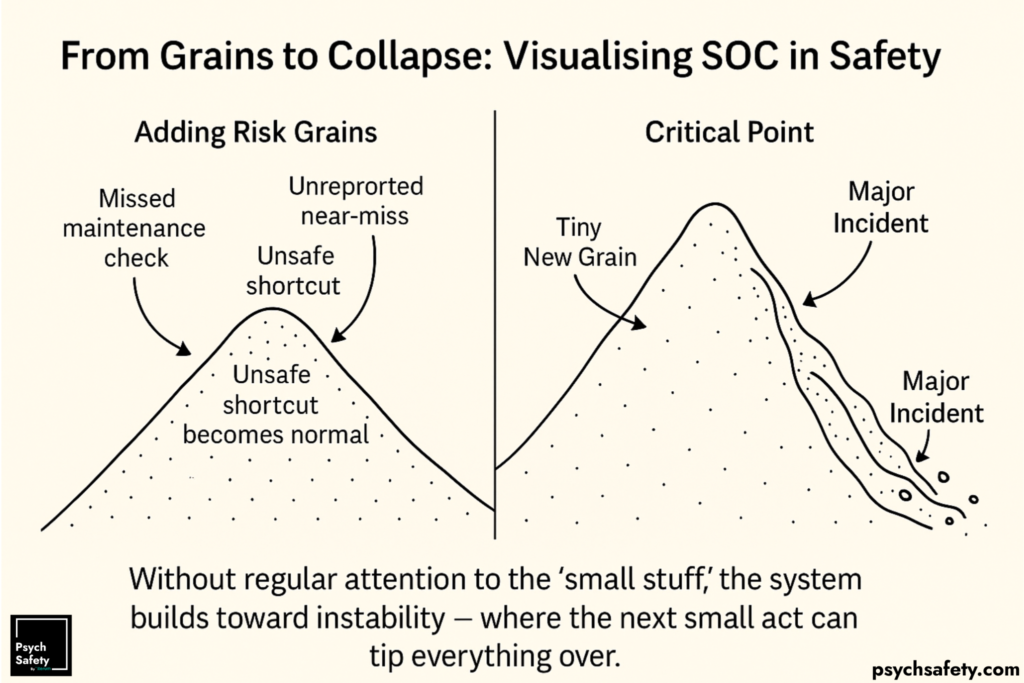

We’ve covered WAI vs WAD, and the different archetypes of work, previously. And I recently recorded a video about WAI/WAD too. I wanted to highlight this excellent example in practice by Claire Cox, which echoes so much of our work with healthcare, particularly maternity departments, who find that policies, SOPs and guidance documents don’t reflect reality. In fact in practice, they often contradict each other – which means that it’s impossible for staff not to violate “Work As Prescribed”, and thus if something goes wrong, the finger of blame immediately points at them for not following procedure (despite it being impossible).

This week’s poem:

First they came, a poetic form of 1946 post-war prose by Martin Niemöller

First they came for the Communists

And I did not speak out

Because I was not a Communist

Then they came for the Socialists

And I did not speak out

Because I was not a Socialist

Then they came for the trade unionists

And I did not speak out

Because I was not a trade unionist

Then they came for the Jews

And I did not speak out

Because I was not a Jew

Then they came for me

And there was no one left

To speak out for me

There are many different versions of this, because Martin Niemöller didn’t actually write it. Instead it’s based on his many impromptu public speeches. Martin Niemöller (1892–1984) was a prominent Lutheran pastor in Germany. Although he initially aligned himself with many far-right and Nazi-leaning ideas in the late 1920s and early 1930s, Niemöller became an outspoken critic of Adolf Hitler after Hitler assumed power in 1933 and Niemöller witnessed the true impact of these ideas. This resistance led to Niemöller spending the final eight years of the Nazi regime in prison and concentration camps. After the war ended, Niemöller often spoke of his own early complicity in Nazism and his eventual change of heart.

The post How We Respond Matters appeared first on Psych Safety.