Spectra of Participation

by Jade Garratt

Engagement and participation are terms we often throw around to mean “getting people’s take on issues that affect them.” But not all participation is created equal. Sometimes, “inviting participation” amounts to little more than asking for feedback on decisions already made; other times, it’s a genuine invitation to co-create solutions.

I first encountered the idea of “spectra of participation” in 2014 while working for a charity. Our manager shared a “Degrees of Consultation” document to clarify the discussion’s purpose (thanks to Shelley Gonsalves for preserving the original source – see below). I was struck by the transparency it fostered: I realised I’d often been asked for input without being clear on what was actually up for change or negotiation.

It turns out there are many versions of this framework, including perhaps the best known one, IAP2’s Spectrum of Public Participation, which clarifies the goal and commitment of work engaging the public in decisions affecting them.

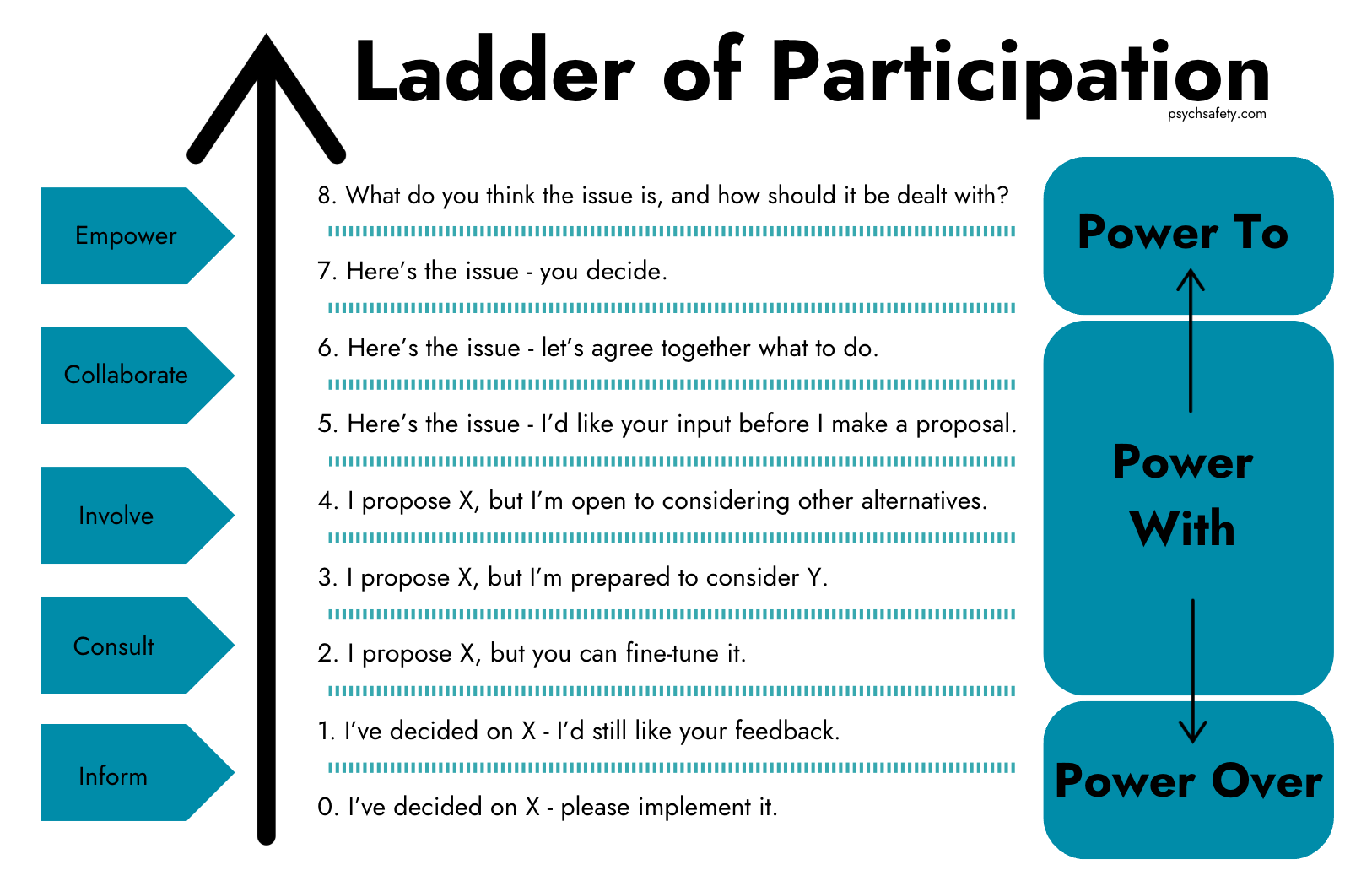

Ladder of participation

Then there’s Bovill and Bulley’s “Ladder of participation in curriculum design,” which is organised vertically to convey a shift from a dictated curriculum toward greater student control over learning.

All of these frameworks capture a similar progression – from minimal input (mere information sharing) to deeper collaboration and co-creation. And while none of them explicitly refer to psychological safety, it’s clear that we need psychological safety in order to successfully foster participation. How safe people feel when sharing feedback or co-creating solutions is pivotal to the success of any participatory process. We generally only engage to the degree that we feel safe to.

The Difference Between Participation and Engagement

Whether we’re talking about the “Degrees of Consultation,” the IAP2 Spectrum, or Bovill & Bulley’s Ladder of Participation – these frameworks focus on participation – how much input are people formally invited to provide? However, participation doesn’t always guarantee engagement, which is about how deeply individuals feel invested in and connected to the process.

- Participation can be seen on a spectrum from minimal (simply informing others after decisions are made) to maximal (co-creating outcomes).

- Engagement is about the quality of that participation—whether people feel safe, motivated, and genuinely committed to sharing their ideas, questions, and concerns.

When psychological safety is missing, higher rungs on the participation ladder may still not translate into real engagement. People can be asked to co-create, but if they sense a risk of blame, judgment, or dismissal they will likely hold back. Conversely, when psychological safety is present, even a modest level of participation can result in meaningful dialogue, richer collaboration, and better outcomes because we can more fully engage with the process.

Why Transparency and Clarity Matter

Going back to that meeting where I first encountered the Degrees of Consultation, we were shown it and told “We’re somewhere between levels 0/1,” in other words, somewhere between “put up and shut up” and “you can tell me what you think but it’s not going to make a difference.” This was probably an unfortunate example to introduce the framework with, but there was at least a transparency to it.

If we’re only seeking to inform, and requesting only minimal input, it is arguably better to be honest about that, so the people we’re talking to don’t feel misled into believing they have more influence than they actually do. When we suspect we’re being asked for input just for show – participation theatre – it erodes trust.

On the flip side, if we understand the level of influence we can have, it lets us engage without fear of being ignored or sidelined. It can help to clarify what is expected (and therefore safe) to share – whether that’s concerns, worries, or new ideas and solutions.

Power Dynamics

If you’re the one determining which level of participation you would like to invite, then you’re probably in a position of power. And considering the spectra can help you to be more intentional about how you conceptualise that power and what you choose to do with it.

As always, the trailblazing Mary Parker Follett sheds light here. She talks about forms of power as:

- Power over is about control or domination – I dictate outcomes for you.

- Power with involves collaboration – We work together to decide.

- Power to is about enabling or empowering others – I give you the trust and agency to act.

We can map each level of participation in these ladders or spectra to Mary Parker Follett’s concept. For instance “0 – I’ve decided X. Please implement it.” sits firmly in the power over realm, while “7 – Here’s the issue. You decide.” aligns with power to. It’s Levels 2 to 6 that encompass the many shades of power with.

Moving Beyond Consultation to Co-creation

These spectra remind us that we can aspire to something different to the power-over structures that many of us are conditioned into accepting and therefore reproducing. This is certainly one of the benefits of Bovill and Bulley’s “Ladder of participation in curriculum design” – for those of us who have been schooled in a traditional way where, on the whole, the teacher controls the curriculum, it might not even occur to us when we become teachers ourselves to question this approach.

And this doesn’t just apply to education. Lots of organisations get stuck at a consultative level of participation: “We propose X, but give us your feedback.” But moving towards real collaboration and empowerment can foster much greater creativity, innovation and ultimately greater ownership too.

What About When it’s Necessary to Inform and Dictate?

There are times when simply sharing information or giving a direct command is the most appropriate and effective approach. In immediate crisis situations (e.g. the ship is on fire, or there’s an emerging global pandemic) it may not be helpful or pragmatic to facilitate a large-scale co-creation of solutions or have lengthy discussions about what the problem actually is. Fortunately, these situations tend to be the exception, not the norm.

So there is a cautionary note here: if spectra of participation are only used to create the appearance of engagement, while the actual power dynamic remains ‘power over’ and participation is restricted to the level you’ve deemed acceptable, you risk weaponising the idea. If team members sense that the real intent of ‘inviting participation’ is to keep them in their place, the power gradient will only steepen and psychological safety will take a hit.

Using Ladders of Participation in Practice

Here’s our version of the Ladder of Participation, inspired by and building on the great work of Andrew Forrest, Rosie Ferguson, the IAP2 Framework and the thinking of Mary Parker Follett:

But if we want teams that feel safe to fully engage and participate in the work we’re doing together (as I assume most of us reading this do!), then simply selecting a rung on the ladder or spectrum isn’t enough. Instead, here are some practical takeaways for working with spectra of participation:

- Be transparent about the level of participation you’re aiming for.

- Ensure your actions match your stated intentions.

- Strive for higher rungs wherever possible – ones that promote power-with and power-to.

- Recognise that psychological safety underpins engagement at every stage, from minimal consultation right through to deep, meaningful co-creation.

To do this well, we need to think hard about genuine power-sharing, clarity of intent, and building an environment where people feel safe enough to participate fully.

References

Forrest, A., & Ferguson, R. Degrees of Consultation. CEE, Cass Business School.

IAP2. Spectrum of Public Participation.

Bovill, C., & Bulley, C. J. (2011). A model of active student participation in curriculum design: Exploring desirability and possibility (p. 180).

Further reading:

Mary Parker Follett and Power

Typologies of Power

Reducing Power Gradients

Psychological Safety in Practice

Six Quality Checks for Team Agreements

Here’s a really useful piece from Helen Sanderson, one of our Psych Safety alumni, on quality checks for team agreements. We bang on quite a lot about team charters, social contracts, team agreements and the like, because they’re a great way to foster psychological safety – both in the collective act of creating them and in the existence of them as artefacts. Helen’s put together an excellent 6-piece checklist to ensure that your team agreements have the greatest utility and effectiveness:

Is it observable? (Can you see/hear it happening?)

Is it observable? (Can you see/hear it happening?)  Is it specific? (Does it describe how the behaviour happens?)

Is it specific? (Does it describe how the behaviour happens?)  Is it jargon-free? (Would a new team member understand it?)

Is it jargon-free? (Would a new team member understand it?)  Is it measurable? (Could we track, assess, or review it?)

Is it measurable? (Could we track, assess, or review it?)  Is it team-focused? (Does it describe collective, not just individual, behaviours?)

Is it team-focused? (Does it describe collective, not just individual, behaviours?)  Is it framed positively? (Does it guide action instead of just saying what not to do?)

Is it framed positively? (Does it guide action instead of just saying what not to do?)

Women-Led Humanitarian Organisations (WLOs)

This is a great piece by Maria Luisa Ramirez, an international psychologist from Bogota who previously working with the Colombian women-led organisation GENFAMI. It highlights how many women-led organisations (WLOs) struggle with limited project funding, preventing them from fully participating in humanitarian design and decision-making. These systemic and structural barriers where international agencies often control funding structures and hold decision-making power, relegate WLOs to consultative rather than participatory roles. As a result, broad psychological safety suffers, with people in WLOs reluctant to challenge donor priorities or advocate for community-driven approaches.

Learning From Incidents (LFI)

I love this piece from John Allspaw on an exemplar of Learning From Incidents (LFI). There’s a lot to take from this, but a few key points that I’d like to highlight are:

- Learning From Incidents (LFI) requires a richer, more nuanced understanding of events, their context, and the varied lessons people take away (because everyone will take away different interpretations and lessons from a single incident).

- The learning shouldn’t be limited to the engineers who responded, nor only to the official incident analysts. Instead, aim to engage and include people across many teams and functions (such as customer service*). Put effort into making write-ups readable, useful and engaging, otherwise people won’t read them.

- Teams should possess the freedom to do what they believe is right.

- Incident interviewing is a learned skill: engineers may need to unlearn certain habits to conduct interviews that reveal deeper insights.

- Learning from incidents is no longer a peripheral concern: it is becoming a central practice in resilient, high-performing organisations.

*When I was CTO at a large event and retail venue, in incident reviews and learning events we would regularly engage people outside tech, including customer service folks, operations and safety crew, finance, and others. This had many benefits:

- We got to foster greater cross-functional relationships.

- People outside tech asked the questions that we didn’t even think to ask.

- Learning was amplified – we learned more things, and more people learned the things.

- People in tech were better able to understand the impact that incidents had on the wider organisation.

- Ultimately, all this led to improved Learning From Incidents.

The post Spectra of Participation appeared first on Psych Safety.