The Chatham House Rule

By Jade Garratt

We always begin our workshops with a social contract. These are important because they make sure at the very beginning, that we’re on the same page in terms of our expectations of each other, we’ve had chance to agree our shared ways of working (or WoW, as one of our brilliant attendees called them recently), and everyone shares the same understanding of the space. It aligns closely to no. 2 in our top ten ways to foster psychological safety: Establish Shared Norms.

This social contract usually looks a bit like this:

We discuss each point in turn, ask if there’s anything we want to add to the agreement, and check that everyone’s happy with the social contract for the session.

One that often takes a little explaining is the Chatham House Rule.

This rule, in its most up-to-date form is as follows:

“When a meeting, or part thereof, is held under the Chatham House Rule, participants are free to use the information received, but neither the identity nor the affiliation of the speaker(s), nor that of any other participant, may be revealed.”

Essentially, the rule tells us that it’s ok to share information and stories from the session when we leave, but not to share who said what.

Where does the Chatham House rule come from?

Chatham House is the name of the London Headquarters of a Think Tank called The Royal Institute of International Affairs. It’s a historic organisation whose stated mission is “to help governments and societies build a sustainably secure, prosperous, and just world“. The Chatham House rule was first created by the organisation in 1927 and has been subject to a number of revisions since, but its purpose remains the same – to facilitate an environment where people can have frank, open and honest discussions about sometimes challenging topics.

Interestingly, it’s said that many Chatham House events do not actually use the Chatham House Rule, but are “on the record”. But the rule is still what most of us best know the organisation for, and it’s been adopted by thousands of different organisations, groups and teams around the world. Chatham House has even translated it into 6 languages – Arabic, Chinese, French, German, Portuguese, Russian and Spanish and say they are working on further translations. Whilst often erroneously referred to as “Chatham House Rules”, it is just the one rule.

Why is the Chatham House Rule helpful for building psychological safety?

Our intention when we run sessions is for people to feel as psychologically safe as is possible within the short-lived group created as part of the workshop. This is important because as part of the sessions, people will often want and need to share personal experiences, anecdotes, mistakes they’ve made at work and other reflections which they may well not want repeating beyond the session, particularly as they could be taken out of context. They may also hold views that don’t align with their organisations’ practices or are critical of the organisations they are part of, and therefore they’ll feel safer speaking freely if they aren’t worried about being quoted on those views. This is also one reason why we don’t record these sessions.

Following the Chatham House rule allows us to have these honest discussions with a good degree of openness and confidence that things we say will not “come back to bite us” after the session. As Chatham House themselves put it, the rule “helps create a trusted environment to understand and resolve complex problems.”

From a learning perspective, The Chatham House Rule makes it explicitly clear that participants are allowed to share information from the workshops afterwards, so that they and we can continue to learn from each other, but without bringing people’s names and reputations into it. We might for example say “in the workshop, someone discussed a difficult issue they raised with their line manager using PACE – I think this could be helpful for our team too” but not “Alex, who is Head of Leadership Development at Charity X, said their boss was really difficult so they need to use assertiveness tools to manage him.”

The Chatham House Rule vs The Vegas Rule

The Chatham House rule is a little different from the Vegas rule, or “What happens in Vegas stays in Vegas!” If the Vegas Rule is used in a meeting or session, it means nothing that is discussed in the session can be shared outside it.

Although arguably knowing all talk is “off the record” might help some people to feel safe speaking up, it’s rarely practical. After all, what’s going to happen as a result of the discussion in the meeting if no one is allowed to talk about it afterwards? In theory, the group have to repeatedly seek permission from the whole group to “break the rule” every time they need to take anything beyond the meeting. In practice, we find the Vegas Rule is more commonly used to silence some of the group and prevent them from talking outside the meeting, while others (those with more power) are trusted to share and use the information appropriately. Plus, from a psychological safety perspective, there are some rather seedy connotations to the Vegas rule, which might not be super helpful in creating the kind of inclusive environment that we’re seeking!

Making the implicit explicit

Generally speaking, whenever we have uncertainty about the consequences of speaking, we err on the side of silence. It often feels safer to say nothing than speak now and regret it later. The Chatham House Rule helps us make implicit assumptions about what is “ok to share” after the session clearer and more explicit. This gives us all confidence about what will happen when we speak, what is ok to share, and crucially, what is not.

Further reading

Psychological Safety Online Workshops

How to Run Psychologically Safe Meetings

Behaviours that foster psychological safety

Top ten ways to create psychological safety

More Feedback Workshops!

We’ve had a lot of demand for more Delivering Effective Feedback workshops, so we’ve scheduled another for January 9th, 2025. This session is scheduled for 10am GMT, so if you’re in Asia, Australia or New Zealand, you can attend without interrupting your sleep!

This Delivering Effective Feedback workshop builds on the foundations of psychologically safe practice in order to use feedback effectively and avoid causing harm.

In our work with teams, we’ve found that between 70% and 80% of feedback is not useful, and some of it is actually harmful. Only 20%-30% of feedback that people receive is actually useful! Primarily, this is simply because feedback is often delivered poorly.

This workshop examines the purpose of feedback, the characteristics of good feedback, traps to avoid, models to use, and practices to employ.

All attendees receive a Credly Badge, a certificate of completion to confirm attendance, further reading, materials and resources used in the session, a copy of the Psychological Safety Action Pack and a licence to use it in your organisation, access to a private alumni group, and some swag! Book here.

Psychological Safety in Practice

Workplace hostility and inclusion

An interesting paper here from Manuela R. Collis and Clémentine Van Effenterre on workplace hostility in respect to hybrid working. They show that people are willing to forgo 15 to 30 percent of their wage to avoid hostile work environments, and this is a stronger effect for women. The converse of this, of course, is that hostile, non-inclusive environments cost employers 15-30% more in wages in order to recruit and retain staff.

Trust and safety in maritime contexts

This paper on trust and safety in shipping by Anne Gausdal and Julija Makarova uses the same framework of trust that we use: the components of cognitive and affective trust, where cognitive trust represents our choice of whom we will trust and why, while affective trust depends on our emotional bonds with another person.

Lack of crews’ trust in the captain affects safety because it may lead to fear of demonstrating a lack of knowledge, fear of raising issues, fear of asking for advice, and fear of calling the captain to the bridge. This can lead to human errors as a result of avoidance of decision-making, or wrong decision-making altogether. Therefore, if trust between managers and employees runs low, human errors increase.

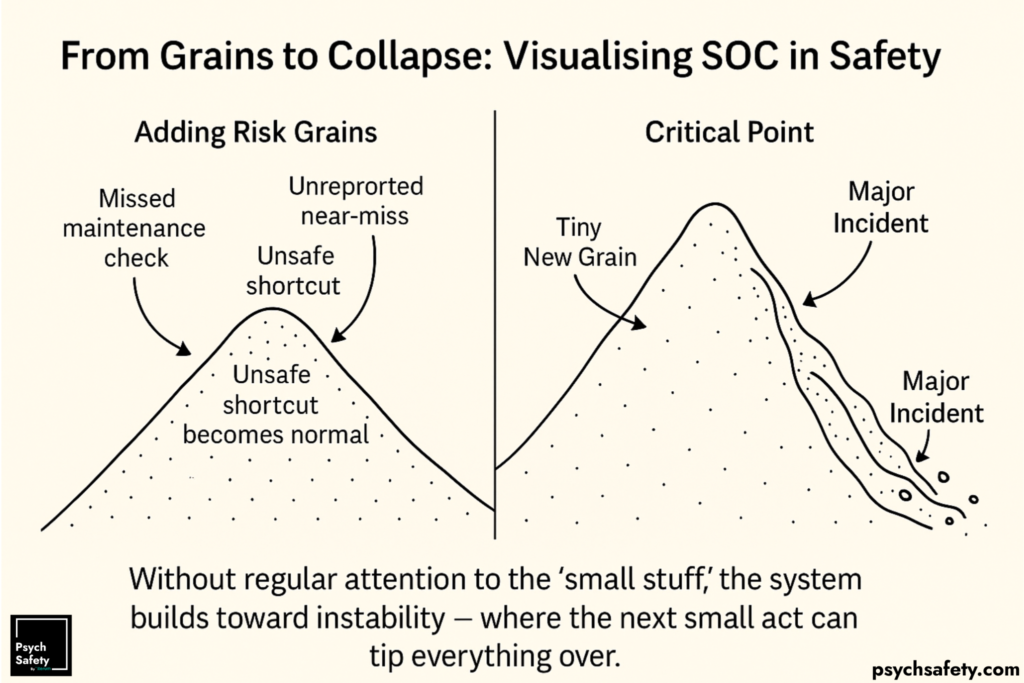

The carefulness knob

I love this piece from Lorin Hochstein on “The carefulness knob”, which frames the ETTO Principle (Efficiency-Thoroughness Trade-Off) as a dial that we can turn one way or the other, in essence trading carefulness for speed. One of the key points is that you can never be 100% careful: Residual risk is inevitable, and complete “carefulness” would mean never delivering anything. Reject the desire for absolute control over the results – we can never completely assure success, whether we’re coding software or flying planes. We instead have to trust people – the experts doing the actual job – to make those tradeoffs implicitly and intelligently.

This week’s poem:

Fascism: I sometimes fear… By Michael Rosen

I sometimes fear that

people think that fascism arrives in fancy dress

worn by grotesques and monsters

as played out in endless re-runs of the Nazis.

Fascism arrives as your friend.

It will restore your honour,

make you feel proud,

protect your house,

give you a job,

clean up the neighbourhood,

remind you of how great you once were,

clear out the venal and the corrupt,

remove anything you feel is unlike you…

It doesn’t walk in saying,

“Our programme means militias, mass imprisonments, transportations, war and persecution.”

The post The Chatham House Rule appeared first on Psych Safety.