Types of Power

In a few previous newsletters, we’ve gotten into power dynamics, power gradients, “power over” vs “power for” and “power to” (see Mary Parker Follett). Steep power gradients are the number one inhibitor of psychological safety, and addressing power gradients is one of the first things to do in order to improve it.

The power gradient may be known by a number of terms across different fields:

- Power gradient

- Power differential

- Authority gradient

- Cross-cockpit authority gradient (in aviation)

- Power distance (at a cultural level)

- Hierarchy differential

- Status asymmetry

In this piece, we wanted to illustrate a few ways in which we categorise power. The better we are able to understand power and communicate that understanding with others, the better placed we are to be able to intervene and address imbalances that degrade team performance, or in the worst cases, cause actual harm to people. This connects to the idea of “power literacy” – if we don’t have the language to talk about power, we can find ourselves powerless to address inequity.

“Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.”

James Baldwin

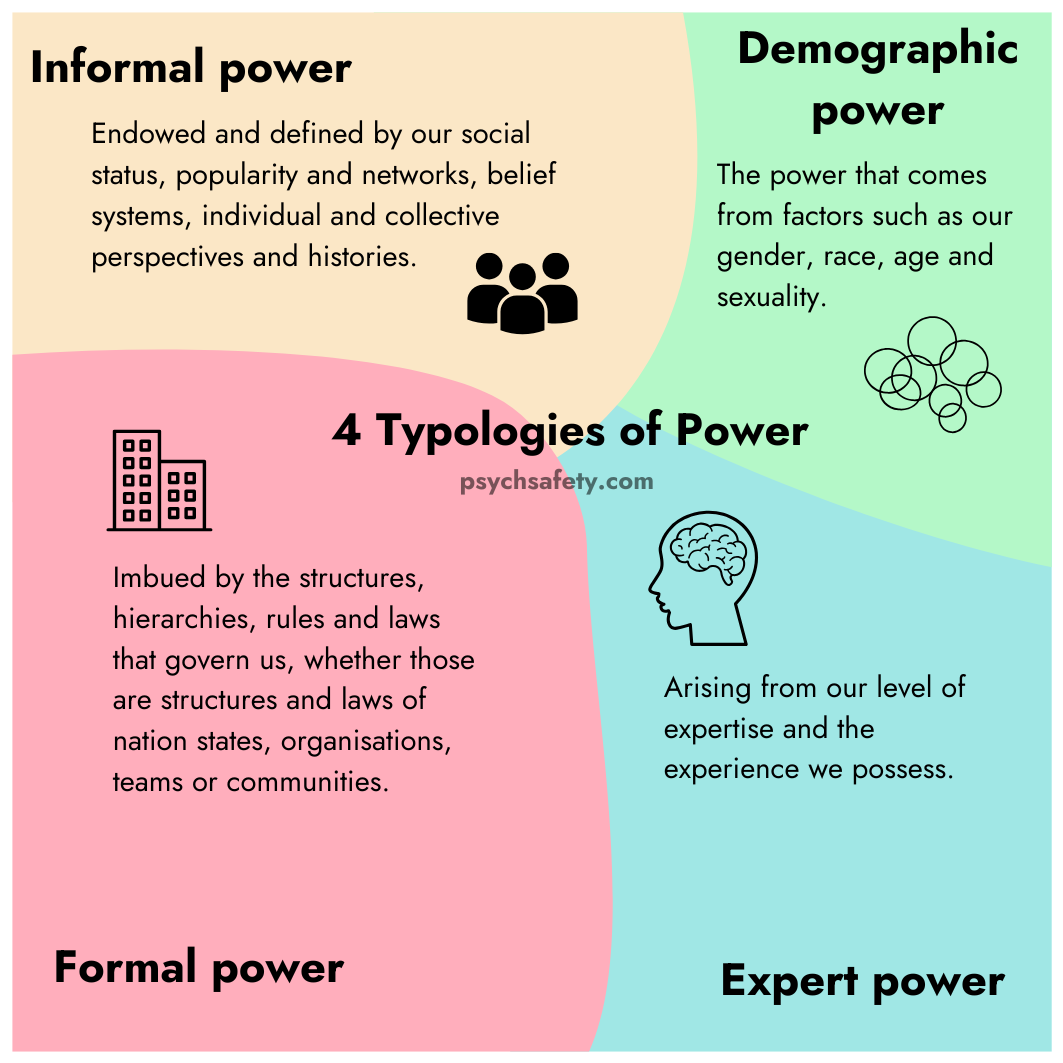

There are many schools of thought in respect to power, and entire papers and books have been written on the topic. At Psych Safety, we try to keep things simple enough to be actionable and practical, whilst granular enough to be meaningful: and we’ve found these typologies to be the most accurate and useful: Formal, Informal, Demographic, and Expert.

Four (of many) Types of Power

- Formal power is imbued by the structures, hierarchies, rules and laws that govern us, whether those are structures and laws of nation states, organisations, teams or communities.

- Informal power is endowed and defined by our social networks, belief systems, individual and collective perspectives and histories. In a work context, even if we are not in a senior role, we might have a degree of informal power because of our popularity and social status with our colleagues.

- Demographic power is the power that comes from factors such as our gender, race, age and sexuality. Depending on the space we are in and the dominant norms of that space, it might be easier for us to influence and have our voices heard if we are (for example) a white, middle-class man.

- Expert power comes from our level of expertise and sometimes the experiences we have had – it is the power given by our knowledge, but of course only works as power when others acknowledge its significance.

These types of power are not independent of each other, and significant imbalances in any type of power usually result in lower levels of psychological safety.

When we take into account these various different types of power, it becomes clear that the formal power structure dictated and described by an organisational hierarchy may not be what the real power in the organisation looks like. In fact, it probably isn’t. It might look more like the picture on the right below…

Ways of Thinking about Power

We’re not the first to examine the different types of power, and how we define power is based upon the work of many folks before us.

In Rousseau’s 18th Century work on the “social contract”, which in this context concerns the legitimacy of the state’s authority to have power over individuals, he wrote that:

“Let us then admit that force does not create right, and that we are obliged to obey only legitimate powers”

In other words, might does not make right, and people have no duty to submit to it. But there are other types of power than simple might alone, and we’re often under no choice but to submit or be influenced by them.

In 1959, social psychologists French and Raven described five bases of power:

1. Legitimate – This comes from the belief that a person has the formal (i.e. legal or political) right to make demands, and to expect others to be compliant and obedient.

2. Reward – This results from one person’s ability to compensate another for compliance, which is essentially a function of wealth.

3. Expert – This is based on a person’s higher levels of skill, expertise and knowledge.

4. Referent – This is the result of a person’s perceived attractiveness, worthiness and right to others’ respect. Think celebrity, charm, or potentially other aspects such as class or age. Social media influencers try to capitalise on this type of power.

5. Coercive – This comes from the belief that a person can punish others for noncompliance. This could be as extreme as military force, or the power of a manager or teacher to punish in some way (this can also be the converse impact of Reward power – for example, by withholding a reward.)

Six years later, Raven added an extra power base:

6. Informational – This results from a person’s ability to control the information that others have access to. Now, in the age of the internet and figures such as Elon Musk and Mark Zuckerberg, this power base is even more relevant, and arguably the most significant of them all.

John Kenneth Galbraith wrote “The Anatomy of Power” in 1983 and more simply classified three types of power:

- Compensatory power, in which submission is bought

- Condign power, in which submission is won by making the alternative sufficiently painful, and

- Conditioned power, in which submission is gained by persuasion.

To put these in more accessible terms, we might think of them as money, force and ideology.

Feminist theory also has a lot to say on power, particularly the less explicit, often unspoken nature of what we call “demographic” power, which is often unacknowledged in organisations, and has a strong connection to the concept of privilege. Deborah Cameron describes an “unmarked” identity as the default, that which requires no explicit acknowledgment or recognition. Heterosexuality, for instance, is unmarked, and assumed as the norm, unlike homosexuality, which is “marked” and requires a signifier to indicate that it is “different”. Similarly, certainly in Western cultures and especially in the business world, masculinity is unmarked, while femininity is marked. Masculine language and presentation is considered the neutral and more powerful standard, whilst feminine language and presentation is considered different, stands out from the norm, and is considered less powerful. Unmarked identities tend to confer privilege.

Formal, Informal, Demographic and Expert Power

Given all this interesting nuance and variation, why do we tend to work with the four categories of Formal, Informal, Demographic and Expert? We have found these are quite an accessible and useful way to talk about power. We tend to intuitively understand them and usually we’re able to address and acknowledge these types of power in our own contexts.

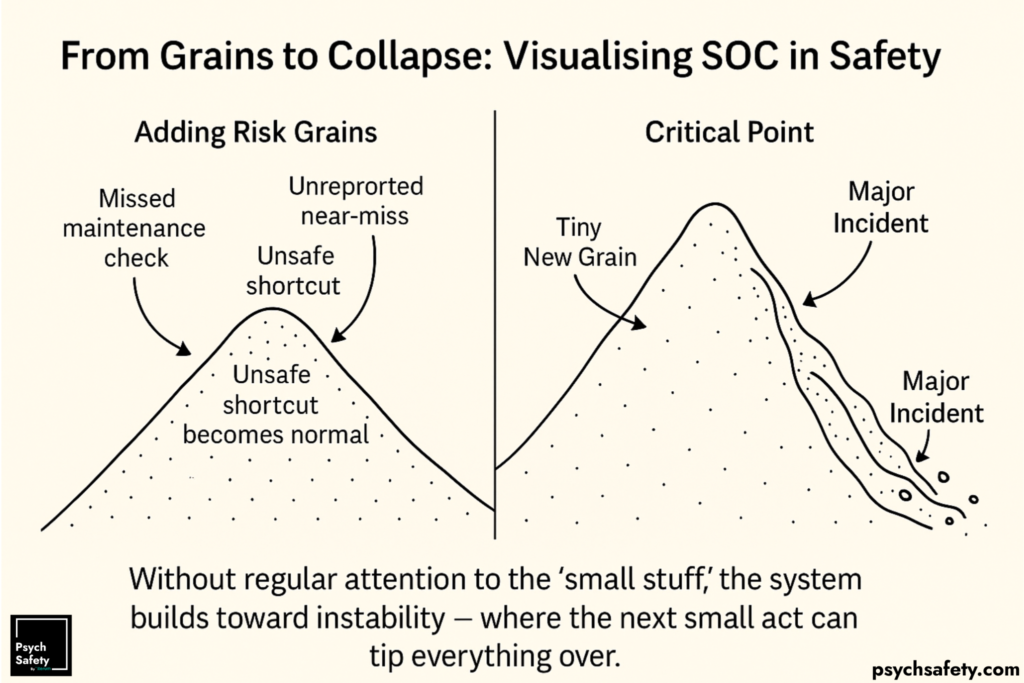

When we know that they can all create problematic power gradients which can be barriers to people speaking up, they also offer us ideas to address them. We may for example be able to structure our teams and organisations in different ways in order to reduce the formal power gradients. When it comes to addressing the influence of informal or demographic power the first, and absolute minimum, we can do is acknowledge that it exists. When we’ve done that, we can look for ways to mitigate it, by amplifying other voices and encouraging diverse perspectives. And by recognising expert power, we can make best use of expertise whilst mitigating its possible effect on quieter or more junior voices (which as we’ve seen, are also essential in order to identify and amplify weak signals).

Power begets power. Power, by its very nature, and in any form, is better able to gain more power when it becomes available. This is why organisations, and society, require strong guardrails and mechanisms to prevent the over-accumulation and monopolisation of power. All of this of course, isn’t to say people who gain power in organisations or in society in general are bad, power-mad, mean and selfish – they’re as much players in the game as anyone else. We all are.

There’s great value in experimenting with different ways of structuring, transferring, flattening and mitigating power. We’ll address some of these ideas in future articles, but it’s worth highlighting in particular that transferring or delegating authority to where the work actually happens is in almost all cases, a good thing.

As we become more power literate, it’s also on us to question how we are, as individuals, using the different types of power we possess for the benefit of others – and always guarding against misuse and abuse of power.

Further Reading:

Power and Mary Parker Follett

Psychological Safety and Privilege

Psychological Safety, Diversity & Inclusion

Amplifying Weak Signals

A team is only as safe as the least safe person

Psychological Safety: Structure and Power

Online Psychological Safety Workshops

We’re excited to announce the next round of workshops will take place in March 2025, with two streams to choose from.

You can choose to attend one or more individual modules, or enrol on the complete Train The Trainer programme.

The Complete Psychological Safety: Train the Trainer is our flagship programme. It goes both broad and deep into the world of psychological safety, using a variety of lenses and perspectives to explore how to understand, foster, build, maintain and measure psychological safety as well as how to inspire others to work on it themselves.

The sessions are delivered via Zoom and we use Miro boards, supplemental handouts, online resources and academic papers to support learning and engagement during the sessions.

Our aim is to ensure you learn as much from the other attendees as you do from us during the session, and we work to create learning spaces in the workshops which are inclusive, accessible and psychologically safe for all. We’ve run these workshops for several years now, and each time we refine and improve them further, making sure you gain the benefit of all our previous experience and learning. Delivering these sessions is one of the most enjoyable aspects of our work, and we want to make sure you have a great time too and get the best possible value from them.

All attendees receive a Credly Badge, a certificate of completion to confirm attendance, further reading, materials and resources used in the session, a copy of the Psychological Safety Action Pack and a licence to use it in your organisation, access to a private alumni group, and some swag! Book here.

Psychological Safety in Practice

Psychological safety and effective learning

Thanks to Jade Garratt for articulating this so well. An article popped up this week that espoused psychological safety as essential for effective collaborative learning. And then, in the same piece, recommended “swift and severe consequences” for breaches of the social contract – which is antithetical to psychological safety itself. There are many reasons we might breach a social contract – by mistake, unknowingly, or with positive intention. If the consequences for flawed interaction within a group and a breach of the social contract are “swift and severe“, then the safest thing to do is not interact at all.

Storytelling for systems change

I love this paper from the Centre for Public Impact, the Dusseldorp Forum and Hands Up Mallee that examines the transformative role of storytelling in community-led, place-based systems change. Focusing on systemic change initiatives in Australia, inspired by the storytelling traditions of First Nations peoples, it explores how storytelling can effectively communicate the impact of community-led systems change and serve as a tool for advocacy, healing, and shifting narratives.

The post Typologies of Power appeared first on Psych Safety.